We then drove by the Bogachiel State Park. Bogachiel State Park is a 127-acre public recreation area on the Bogachiel River four miles south of the city of Forks on Highway 101 in Clallam County, Washington. The state park was established in 1931.

Next we crossed the bridge over the Calawah River (see below). The Calawah River is a 31 mile tributary of the Bogachiel River in Clallam County of Washington, on its Olympic Peninsula. Its two major tributaries are the South and North Forks Calawah River. The river drains an unpopulated portion of the low foothills of the Olympic Mountains and its entire watershed consists of virgin forest. The river's name (Calawah) comes from the Quileute word (qàló?wa) meaning "in between", or "middle river".

We were soon at the turnoff for the Olympic National Park.

We followed the highway along the Northwest Coast.

Just before crossing another bridge, we saw the sign for the Olympic National Park - Lake Ozette. Lake Ozette is the largest unaltered natural lake in Washington state at 11.4 square miles. The Makah name for Lake Ozette was Kahouk meaning "large lake". At 8 miles long and 3 miles wide, Lake Ozette is contained within the northern boundary of the Olympic National Park's coastal strip. It is 29 feet above sea level and is drained by the Ozette River in the north end. Ozette, Washington, lies at the north end of the lake. At 331 feet deep, its bottom lies more than 300 feet below sea level. There are three islands on Lake Ozette: Tivoli, Garden Island, and Baby Island.

We then drove by the Klahowya Campground, just before another bridge that crossed the Sol Duc River (see below). The Sol Duc River is a river in Washington. About 78 miles long, it flows west through the northwest part of the Olympic Peninsula, from the Olympic Mountains of Olympic National Park and Olympic National Forest, then through the broad Sol Duc Valley. Near the Pacific Ocean the Sol Duc River joins the Bogachiel River, forming the Quillayute River, which flows about 4 miles to the Pacific Ocean at La Push.

Although the Quillayute River is short, its large tributary rivers—the Sol Duc, Bogachiel, Calawah, and Dickey Rivers—drain the largest watershed of the northern Olympic Peninsula, 629 square miles. The Sol Duc's watershed is the largest of the Quillayute's tributaries, at 219 square miles. The Sol Duc River's main tributaries are its two forks, the North Fork Sol Duc River and the South Fork Sol Duc River. Other notable tributaries include Bear Creek, Beaver Creek, and Lake Creek.

Much of the Sol Duc River's watershed is valuable timber land. Most of the forests have been logged at least once. The forests within Olympic National Park are protected. U.S. Route 101 follows the Sol Duc River for many miles through Olympic National Forest and the Sol Duc Valley to the vicinity of Forks. The city of Forks is so named due to the close convergence of the Sol Duc, Bogachiel, and Calawah Rivers.

We're now in Sol Doc Valley, and close to the Sol Doc Hot Springs Resort.

We followed the signs to the Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort.

We turned left to go on Sol Duc Hot Springs Road (see above) and soon came to the sign that welcomed us to Soleduck Valley (see below).

We had to show our America The Beautiful - National Parks and Federal Lands Lifetime Senior Pass that allowed us to get in free. The Sol Duc Resort Lodge is now 12 miles ahead.

Here we turned right to go to the Sol Duc Hot Springs.

At the Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort you can soak up the surroundings as the resort offers three Mineral Hot Spring soaking pools and one Freshwater Pool. The spring water comes from rain and melting snow, which seeps through cracks in the sedimentary rocks where it mingles with gasses coming from cooling volcanic rocks. The mineralized spring waters then rise to the surface along a larger crack or fissure.

We walked inside the Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort and found out that the electricity was off, so the hot springs were closed at the moment. The pictures below show what the hot springs looked like.

It was ok that the hot springs were closed because we could still walk the Sol Duc Trail to the Sol Duc Falls that were 0.8 of a mile away (or a 1.6-mile out-and-back trail) near Joyce, Washington.

While we were hiking to Sol Duc Falls, we marveled at the old-growth trees amid a lush rain forest landscape. The Sol Duc Valley in Olympic National Park has it all—towering trees, cascading waterways, alpine lakes, snowcapped peaks and wildlife.

The trail to Sol Duc Falls began beyond the Sol Duc Hot Springs and Resort at the end of the road. The impressive Sol Duc Hotel once stood at the site of the current hot springs and resort. Opened in 1912, the five-star hotel and resort drew crowds from all over the world until it was destroyed by fire in 1920.

From the trailhead, we followed the wide, well-maintained path through the forest, wandering beneath a dense forest canopy and among every shade of green. We crossed a small stream on a bridge, and paused to enjoy the water tumbling over moss-covered rocks. Sol Duc Falls announced itself with a roar prior to coming into our view. Sol Duc Falls splits into as many as four channels as it cascades 48 feet into a narrow, rocky canyon depending on the water volume.

The trail to the Sol Duc Falls contained many small steps and was covered in tree roots in some areas.

The trail tooks us through a lush rainforest-type atmosphere with ferns and moss growing everywhere. It was so peaceful!

Some areas of the trail were boardwalks over mossy areas, while other areas of the trail were rocks and boulders.

We kept following the trail and the signs. Just before the falls we came to a shelter.

The Canyon Creek Shelter, also known as the Sol Duc Falls Shelter, is a rustic trail shelter in Olympic National Park. It is the last remaining trail shelter built in the park by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) from Camp Elwha. The shelter was built in 1939, shortly after Olympic National Park was established from the U.S. Forest Service-administered Mount Olympus National Monument. Two similar shelters were built at Moose Lake and Hoh Lake, neither of which survive. The one-story log structure is T-shaped, with a projecting front porch crowned by a small cupola. The shelter is open to the front porch. The shelter was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 13, 2007.

Shown above and below is the Canyon Creek Shelter in Olympic National Park near Soleduck Falls.

Shown above is the viewing platforms and bridge at Sol Duc Falls. And then shortly after that, we were at the Sol Duc Falls.

An iconic landmark, Sol Duc Falls is Olympic National Park’s most famous and photographed waterfall. The falls tumble about 40 feet into a tight rocky slot, but what really makes them stand out is their unique shape. The Sol Duc River abruptly flows at a right angle careening into three or four chutes (depending on water flow) into the gorge below.

Shown above is Shirley in front of Sol Duc Falls, while below is both Shirley and Mel in front of the Sol Duc Falls.

The Sol Duc Falls were gorgeous.

After standing and viewing and listening to the Sol Duc Falls, we started our walk back the trail to where we began.

Shown above is a type of tree fungus or mushrooms that get their nutrients by digesting dead or decaying organic matter such as leaves, pine needles, and wood -- also known as saprobes. Saprobic fungi play a major role in breaking down and recycling wood and other forest debris, creating healthy soil, and freeing up nutrients for microbes, insects, and growing plants. The above fungus is a northern red-belted conk, which has a tough and woody appearance and is white to cream on the underside with a brownish top. This mushroom is perennial and persistent, forming a new pore surface each year and you can even count the lines on the upper surface to estimate the age of the mushroom!

The sign above on the trail states that wilderness camping permits and bear canisters are required for overnight trips along this trail.

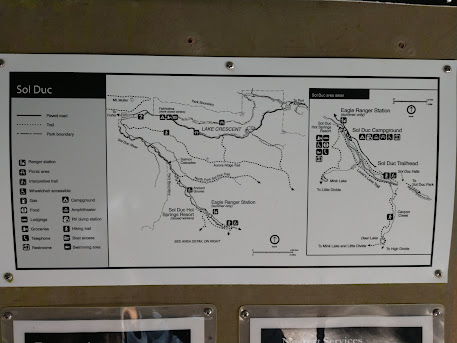

Shown above and below are maps of the trail to Sol Duc Falls.

We are now back on the road and are heading to Lake Crescent. Lake Crescent is a stunning 624-feet deep, glacier-carved lake, and is officially the second deepest lake in Washington. It is one of the iconic destinations of Olympic National Park. The crystal-clear lake is outlined with a stunning forested mountain range.

Lake Crescent is known for its brilliant blue waters and exceptional clarity, caused by low levels of nitrogen in the water which inhibits the growth of algae. It is located in a popular recreational area that is home to several trails, including the Spruce Railroad Trail, Pyramid Mountain trail, and the Barnes Creek trail to Marymere Falls. The Spruce Railroad Trail follows the grade of what was once the tracks of a logging railroad along the shores of the lake. Following this trail on the north side of the lake, one can find the entrance to an old railroad tunnel which is now part of the Spruce Railroad Trail that also provides access to "Devils Punch Bowl", a popular swimming and diving area.

The lake was formed when glaciers carved out deep valleys during the last Ice Age. Initially, the Lake Crescent valley drained into the Indian Creek valley and then into Elwha River. Anadromous fish such as steelhead and coastal cutthroat trout migrated into the valley from lower waters.

Approximately 8,000 years ago, a great landslide from one of the Olympic Mountains dammed Indian Creek, and the deep valley filled with water. Many geologists believe that Lake Crescent and nearby Lake Sutherland formed at the same time, but became separated by the landslide. This theory is supported by Klallum tribe legend which tells a story of Mount Storm King being angered by warring tribes and throwing a boulder to cut Lake Sutherland in two, resulting in Lake Crescent. The results of the landslide are easily visible from the summit of Pyramid Mountain. Eventually, the water found an alternative route out of the valley, spilling into the Lyre River, over the Lyre River Falls, and out to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Shown above is the view of the ancient landslide that dammed Lake Crescent.

It is not certain whether the lake was named for its crescent shape or for its proximity to Crescent Bay, which was named by Henry Kellett in 1846. In 1849 two British–Canadian fur trappers, John Sutherland and John Everett forged inland from Crescent Bay. The two lakes they found became known as Lake Sutherland and Everett Lake. Later, Everett Lake was renamed Lake Crescent. It has also been known as Big Lake and Elk Lake.

In 1890, while the Port Crescent Improvement Company was promoting its townsite near the lake, M.J. Carrigan started the Port Crescent Leader to help boost the town. He wrote of the beautiful lake, which he called Lake Crescent, and the name soon became well-established. The lake was included in the Olympic Forest Reserve in 1897, designated as a recreation area in 1921, and finally included in Olympic National Park in 1938.

We drove along Lake Crescent for quite awhile.

We drove by the Olympic National Park's East Beach and Log Cabin Resort. The Log Cabin Resort offered rustic, yet charming accommodations on the shores of Lake Crescent nestled in old-growth cedars and firs (see below).

We then drove by the sign for the Elwha Valley, which appeared to be closed to vehicle traffic beyond the Madison Falls parking lot at the park boundary due to extensive flood damage/road washout. The Elwha is the Olympic Peninsula's largest watershed and prior to the construction of two dams in the early 1900s, was known for its impressive salmon returns. The Elwha Valley is located in the central northern area of Olympic National Park and is 11 miles west of Port Angeles, Washington.

Next, we were in Port Angeles, Washington, where the mountains greet the sea. Port Angeles is a city and county seat of Clallam County, Washington with a population of 19,960.

(Aerial view of downtown Port Angeles looking towards the Olympic Mountains.)

The city's harbor was dubbed Puerto de Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles (Port of Our Lady of the Angels) by Spanish explorer Francisco de Eliza in 1791. By the mid-19th century, after settlement by English speakers from the United States, the name was shortened to its current form, Port Angeles Harbor.

(Shown above is an aerial view of the Port of Port Angeles.)

We drove by the Clallam County Courthouse that was built in 1914 (see below).

We then ate lunch at the Taco Bell/KFC in Port Angeles, Washington(see below).Mel had a taco combo while I had chicken fingers from KFC.

After eating lunch, we then turned right and drove toward the Hurricane Ridge Visitor Center, stopping at the Wilderness Information Center first. It is there that we found out that the Hurricane Ridge Visitor Center that was located within the Hurricane Ridge Day Lodge had burned down.

We went inside the Wilderness Information Center.

The information board outside the Wilderness Information Center told us why there was limited access to Hurricane Ridge because of the fire that burned down the Hurricane Ridge Day Lodge in May.

We looked around inside the Wilderness Information Center and then watched the film, "Mosaic of Diversity," which showcased the incredible diversity of flora and fauna at Olympic National Park.

We then went outside the Wilderness Information Center to look at the Beaumont Cabin.

The storyboard above told us about the Beaumont Cabin. This log cabin was built in 1887 about a mile south of here by Mr. and Mrs. Elliott Beaumont as a home while "proving up" on a 160-acre Government homestead. They lived in this cabin for almost 40 years. The cabin was donated by Mr. Don Newman to the Clallam County Historical Society to be used as an exhibit of pioneer life on the Olympic Peninsula. It was moved from the original site on his property in 1962 by members of the Society to behind the Olympic National Park Visitor's Center and they have restored and furnished the cabin with representative furnishings of the pioneer period 1850-1900.

Shown above is the Baldwin Locomotive Whistle and Bell outside the Beaumont Cabin.

Shown above is the plaque located next to Baldwin Locomotive Whistle and Bell. While shown below in the next several pictures is the inside of the Beaumont Cabin.

And now we are on our way to Hurricane Ridge.

We drove through the Heart O' the Hills area and then to the entrance station and we were on our way to Hurricane Ridge, which was 17 miles away.

Shown above is entering Olympic National Park through the Heart o' the Hills entrance station south of Port Angeles, Washington.

The drive to Hurricane Ridge was beautiful, we saw several deer, and enjoyed driving through the short tunnels along the way.

The drive up was spectacular and very scenic with all the beautiful trees and foliage along the way. However, the road was very curvy, very steep, and a very slow drive to the top.

The most important thing to do at Hurricane Ridge is to take in the view!

The stop at Hurricane Ridge really taught us the true meaning of the phrase, “The mountains are calling!” This dramatic landscape made us feel worlds away from bustling cities like Seattle. The drive up was breathtaking and so was the view at the top (see pictures below).

The white snow covered peak in the picture above is Mount Olympus.

(Close-up of Mount Olympus.)

(Mountain meadows on Hurricane Ridge.)

(View of Mount Olympus from Hurricane Ridge.)

The Hurricane Ridge Day Lodge was a two-story, 12,201 square foot, historic structure built in 1952. It burned down on May 7, 2023.

Before the fire, the Hurricane Ridge Visitor Center was an iconic landmark in Olympic National Park. Starting from sea-level in Port Angeles, Washington, a scenic 45 minute, 17-mile drive lead you to the well-positioned Hurricane Ridge Visitor Center at 5,242 feet with sweeping vistas of the interior Olympic Mountains and views of Mount Olympus, the largest peak in Olympic National Park at 7,980 feet.

(The remains of the Hurricane Ridge Day Lodge in the Olympic National Park.)

Shown above is a map of the Hurricane Ridge area. We walked along the Hurricane Ridge trail for a little ways.

Shown above is a young deer wandering around Hurricane Ridge, while below is another one we saw at Hurrican Ridge with Mount Olympus behind it.

(Shown above is a view of the Strait of Juan de Fuca from Hurricane Ridge.)

The Strait of Juan de Fuca (officially named Juan de Fuca Strait in Canada) is a body of water about 96 miles long that is the Salish Sea's main outlet to the Pacific Ocean. The international boundary between Canada and the United States runs down the center of the Strait. It was named in 1787 by the maritime fur trader Charles William Barkley, captain of Imperial Eagle, for Juan de Fuca, the Greek navigator who sailed in a Spanish expedition in 1592 to seek the fabled Strait of Anián.

Shown above is the Olympic Mountains and Mount Olympus, which is the tallest and most prominent mountain in the Olympic Mountains of western Washington state. It is located on the Olympic Peninsula and is the central feature of Olympic National Park. Mount Olympus reaches 7,956 feet above sea level, ranking it 5th in the state of Washington.

What’s odd about this prominent mountain is that you can only see it from Hurricane Ridge and other mountain peaks. The mountain is hidden from view in Seattle, Tacoma, Olympia, Sequim, and even Port Angeles, with other mountains obstructing the view. It is the third most isolated peak in Washington State.

After we had finished seeing what we wanted to see at Hurricane Ridge, we started back down. The journey back down was just as beautiful as it had been on the way up.

It is awesome to see the variations of green in the trees on the mountainside (see above).

We once again went through the short tunnels.

And we are now back in Port Angeles, Washington.

And we are now on our way back to our campsite in Ocean City.

We drove by the Dungeness National Wildlife Area. The Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge is located near the town of Sequim in Clallam County in Washington on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The refuge is composed of 772.52 acres which include Dungeness Spit, Graveyard Spit, and portions of Dungeness Bay and Harbor. Dungeness Spit is one of the world's longest natural sand spits, 6.8 miles long and very narrow. A lighthouse, the New Dungeness Light, built in 1857, is located near the end of the spit.

The refuge provides habitat for a variety of wildlife species with more than 250 species of birds and 41 species of land mammals. The bay and estuary of the Dungeness River supports Waterfowl, Wader, Shellfish, and harbor seals. Anadromous fish like Chinook, Coho, pink salmon and chum salmon occur in the waters of Dungeness Bay and Harbor.

We were soon at Sequim -- which gives us a Roosevelt Elk Welcome! Sequim is a town of 7,500 in the northern-most part of the Olympic Peninsula. Sequim Bay is to the east of town and is part of the larger Strait of Juan de Fuca which separates the US and Canada. The town’s notoriety is two-fold: acres and acres of lilac fields abound and a herd of 100 Roosevelt Elk roam the area freely. The elk have been tagged with a transmitter that “sets-off” a series of red lights on Highway 101 in warning of the herd approaching the roadway.

We drove by the John Wayne Marina. This Sequim Bay beautiful public marina site (see pictures below) was built in 1985 on land donated by actor John Wayne's family as a reminder of his love for the area and the times he brought his yacht to Sequim.

Next we went by the Whidbey Island Ferry and we continued toward Quilcene and Olympia on Hwy 101 South.

We have now entered Quilcene, Washington.Quilcene is an unincorporated community in Jefferson County, Washington with a population of 596. The community is located on the Olympic Peninsula at the head of Quilcene Bay, an arm of the seawater-filled glacial valley of Hood Canal. The Olympic National Forest lands in Quilcene hold Douglas fir, spring-blooming Pacific rhododendrons, Oregon grape, and salal.Quilcene oysters are named after the community with Quilcene having one of the largest oyster hatcheries in the world. Early inhabitants of the area were the Twana people, inhabiting the length of Hood Canal, and rarely invading other tribes.

Around 4:30 p.m. in the afternoon, we are 54 miles from Shelton and 76 miles from Olympia.

We drove by the Hood Canal Ranger District - Quilcene Station, which is an Olympic National Forest ranger station located in Quilcene, Washington.

We crossed the Hamma Hamma River Bridge (see above and below). This is one of two nearly identical bridges that cross the north and south Hamma Hamma River and are within sight of each other. The bridges are rare examples of concrete through arch bridges (often called rainbow arch bridges). These two bridges are particularly rare because they function as three hinged arch bridges, which is uncommon among rainbow arch bridges.

We drove along Hood Canal. Hood Canal is a fjord forming the western lobe and one of the four main basins of Puget Sound in the state of Washington. It is one of the minor bodies of water that constitute the Salish Sea. Hood Canal is not a canal in the sense of an artificial waterway—it is a natural feature.Hood Canal is long and narrow with an average width of 1.5 miles and a mean depth of 177 feet. It has 212.9 miles of shoreline and 16.4 square miles of tideland. Hood Canal extends for about 50 miles southwest from the entrance between Foulweather Bluff and Tala Point to Union, where it turns sharply to the northeast, a stretch called The Great Bend. It continues for about 15 miles to Belfair, where it ends in a shallow tideland called Lynch Cove.

Several rivers flow into Hood Canal, mostly from the Olympic Peninsula, including the Skokomish River, Hamma Hamma River, Duckabush River, Dosewallips River, and Big Quilcene River. Small rivers emptying into Hood Canal from the Kitsap Peninsula include the Union River, Tahuya River, and Dewatto River.

We now drove by Potlatch State Park. Potlatch State Park is a 57-acre Washington state park located on Hood Canal near the town of Potlatch in Mason County.

We are now 10 miles from Shelton and 33 miles from Olympia.

We crossed the bridge over the Skokomish River. The Skokomish River is a river in Mason County, Washington. It is the largest river flowing into Hood Canal, a western arm of Puget Sound. From its source at the confluence of the North and South Forks, the main stem Skokomish River is approximately 9 miles long. The longer South Fork Skokomish River is 40 miles, making the length of the whole river via its longest tributary about 49 miles. The North Fork Skokomish River is approximately 34 miles long. A significant part of the Skokomish River's watershed is within Olympic National Forest and Olympic National Park.

Lastly, we drove by Skokomish River Rec Area. After that we still had a little under two hours of travel time until we were back at our campground at 7:00 p.m. (after stopping for gas at Safeway in Ocean Shores).

The map shown above shows the route we drove today starting at Ocean City, Washington and proceeding northwardly and clockwise around until we returned back to Ocean City, Washington. We traveled 397 miles during the 12-hour trip today.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment