Monday, September 25, 2023

It's cloudy and rainy today. The temperature started out at 57 degrees and would only reach 64 degrees.

We left Ocean City, Washington at 8:15 a.m. and are headed to Whalers Rest Thousand Trails in South Beach, Oregon, which is almost 250 miles away.

We drove by the Willapa River. The Willapa River is a river on the Pacific coast of southwestern Washington that is approximately 20 miles long. It drains an area of low hills and a coastal plain into Willapa Bay, a large estuary north of the mouth of the Columbia River. The river rises in the Willapa Hills in southeastern Pacific County, approximately 25 miles west of Chehalis. It flows northwest in a winding course past the small communities of Willapa and Raymond. It enters the northwest end of Willapa Bay at South Bend. The name is that of the Willapa people, an Athapaskan-speaking people, now extinct, who occupied the valley of the river and also the prairies between the headwaters of the Chehalis and Cowlitz Rivers.

We are now passing through South Bend, Washington. South Bend is the county seat of Pacific County, Washington with a population of 1,637. The town is widely-known for its oyster production and scenery. South Bend was officially incorporated on September 27, 1890. The name of the city comes from its location on the Willapa River. The county seat was relocated from Oysterville to South Bend in 1893.

(Pacific County Courthouse in South Bend, Washington.)

The Pacific County Courthouse is on the National Register of Historic Places. The old South Bend Courthouse was the site of the first and only execution carried out in Pacific County when convicted murderer Lum You was hanged in 1902.

We are now 47 miles from Astoria, Oregon.

We drove by the exit to Lewis and Clark National Park.

Long Beach is now 16 miles away, while Ilwaco is 17 miles away.

It is raining pretty steady now as we drive by the exit to the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge.

We turned left following the detour sign to US Hwy 101 Alt to Astoria, Oregon.

Astoria is now 14 miles away.

We continued to follow the detour to the left to US Hwy 101 South to Chinook and Astoria. Then at the stop sign we turned left (see below).

Astoria is now 13 miles away, while Longview is 80 miles away.

We then entered Chinook. Chinook is a census-designated place in Pacific County, Washington, with a population of 466. Chinook was the site of the first court in Pacific County in 1853, as well as the county's first salmon cannery in 1870. Chinook was once a wealthy town based on the salmon harvest. There was no road connection to Ilwaco until 1891, when the bridge was completed across the Chinook River. Later, the Ilwaco Railway and Navigation Company built a narrow gauge railroad from Megler to Ilwaco, passing down the main street of Chinook. The railroad was dismantled in 1931.

The village of Chinook, located on the shore of the Columbia River at its mouth, grew up around the wealth of salmon that once swarmed upriver. Since the days before written memory, the first peoples of the region — the Chinook Indian Nation — have lived here, harvesting those famous fish. Their cedar long houses were old when Lewis and Clark visited in 1806.

From the late 1500s on, nations sent seafarers in small ships to sail the world seeking riches and new territory. The Pacific Northwest between California and what would become British Columbia was one of the very last corners of the world so explored. In 1792 Captain Robert Gray of Boston found his way across the treacherous Columbia River bar; in 1805 Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and other members of the Corps of Discovery paddled downriver to the Chinook village; and in 1811 the men of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company struggled in over the bar in 1811, settling on the south shore at what became Astoria.

In those days the main channel of the Columbia ran close to the north shore, flowing around Sand Island and on away up east. That shoreline is where the fishermen settled, first the Natives at what Lewis and Clark called “Middle Station,” just east of the highway tunnel; then retirees of the Hudson’s Bay Company (the successor to the Pacific Fur Company); then European immigrants who knew how to earn a living catching, salting and selling fish.

The area of north shore settlement between Point Ellice (where the Astoria-Megler Bridge reaches the Washington shore) and Fort Columbia (where the highway goes through the tunnel) was generally known as “Chinookville”; it was the second seat of Pacific County, Oregon Territory, between 1852 and 1854.

In the 1850s Irish immigrant P. J. McGowan arrived, bought land from early settler Catholic priest Fr. Lionnet, and filed for a donation land claim. McGowan began catching and salting salmon for export; later he built a successful salmon cannery. In the early 1900s he also built St. Mary’s Catholic Church which stands by the roadside just upriver of the highway tunnel.

(Shown above is the two-story Chinook Observer building constructed in 1905. It was a major landmark in early downtown Chinook.)

As this remote North American corner began to be settled by Europeans and “Bostonmen,” and newspapers began to take note and we find reference to the village of Chinook. In the early 1850s, James G. Swan joined a friend from Shoalwater Bay (now Willapa Bay) to watch Chinook Indians seine (fish) for salmon on the Columbia River shore. Immigrant fishermen soon developed “fish traps” — an arrangement of pilings sunk into the river bed, from which nets were suspended across the incoming tide. Upstream-swimming salmon ran afoul of the net; at low tide the trapmen took the stranded fish to the buyer’s scow, or to the cannery, and were paid or received credit on the spot. No inventory, no storage, fresh fish. Neat!

Shown above -- McGowan was a major employer in the Chinook area starting around the Civil War. “Quinat” was the name of a species of salmon — a large version of Chinook — now possibly extinct.

Early-day canneries — the region once had 39 — became an industry and some local fishermen and canners got rich. The rumor continues to this day that in those late 19th century times Chinook was the richest town, per capita, in the United States. It could have been. Not long after that, the U.S. Army bought Chinook Point — Scarborough Head — and built Fort Columbia. First it was to help Ft. Adams and Ft. Canby protect the mouth of the Columbia during the Spanish-American War; then it was to serve the same purpose in both World War I and World War II.

The prosperous citizens of the lively community of Chinook valued family life, and that included the education of their children. They chose to spend some of their wealth on a solid school for their youngsters.

(One of Chinook’s earliest public schools was the start of a proud tradition.)

In the decades before 1920, the community had several editions of a K-8 school in the Chinook farmland east of the village known today. Chinook was its own school district, and in the 1910s it decided to build a gymnasium. (Basketball, in particular, was a much-loved community sport; soldiers stationed at Fort Columbia and teams from other villages played a serious game. The rains of winter dictated an indoor playing court.)

Next we drove by Fort Columbia State Park, which is a public recreation area and historic preserve at the site of former Fort Columbia, located on Chinook Point at the mouth of the Columbia River in Chinook, Washington. The 618-acre state park features twelve historic wood-frame fort buildings as well as an interpretive center and hiking trails. The park's grounds are located over a tunneled section of US Hwy 101.

Fort Columbia was built from 1896 to 1904 to support the defense of the Columbia River. The fort was constructed on the Chinook Point promontory as part of a "triangle of fire" defensive strategy that included Fort Canby and Fort Stevens. Fort Columbia was declared surplus at the end of World War II and was transferred to the custody of the state of Washington in 1950.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Battery 246 was outfitted to serve as a Civil Defense Emergency Operating Center and was one of several possible locations the governor could use in an emergency. In 1993, the park received a pair of 6-inch guns that were transferred to Battery 246 from the former Fort McAndrew, Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland, Canada.

Fort Columbia State Park is considered one of the most intact historic coastal defense sites in the U.S.

(Shown above are the historic wood-frame buildings at Fort Columbia State Park.)

We drove through a tunnel and continued on our way on US Hwy 101.

Soon in the distance on the horizon, we could see the Astoria-Megler Bridge crossing the Columbia River.

The Astoria–Megler Bridge is a steel cantilever through truss bridge in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States that spans the lower Columbia River. It carries a section of US Hwy 101 from Point Ellice near Megler, Washington to Astoria, Oregon. The bridge opened in 1966 and is the longest continuous truss bridge in North America.

The bridge is 14 miles from the mouth of the river at the Pacific Ocean. The bridge is four miles in length, and was the final segment of US Hwy 101 to be completed between Olympia, Washington, and Los Angeles, California. Ferry service between Astoria and the Washington side of the Columbia River began in 1926. The Oregon Department of Transportation purchased the ferry service in 1946. This ferry service did not operate during inclement weather and the half-hour travel time caused delays. In order to allow faster and more reliable crossings near the mouth of the river, a bridge was built jointly by the Oregon Department of Transportation and Washington State Department of Transportation.

Construction on the structure began on November 5, 1962, and the concrete piers were cast at Tongue Point, four miles upriver. The steel structure was built in segments at Vancouver, Washington, ninety miles upriver, then barged downstream where hydraulic jacks lifted them into place. The bridge opened to traffic on July 29, 1966, marking the completion of US Hwy 101 and becoming the seventh major bridge built by Oregon in the 1950s–1960s; and ferry service ended the night before.

On August 27, 1966, Governors Mark Hatfield of Oregon and Dan Evans of Washington dedicated the bridge by cutting a ceremonial ribbon. The four-day ceremony was celebrated by 30,000 attendees who participated in parades, drives, and a marathon boat race from Portland to Astoria. The cost of the project was $24 million, equivalent to $166 million in 2022 dollars, and was paid for by tolls that were removed on December 24, 1993, more than two years early.

The bridge is 21,474 feet in length and carries one lane of traffic in each direction. The cantilever-span section, which is closest to the Oregon side, is 2,468 feet long, and its main (central) span measures 1,233 feet. It was built to withstand 150 mph wind gusts and river water speeds of 9 mph. As of 2004, an average of 7,100 vehicles per day use the Astoria–Megler Bridge.

The south end is beside what used to be the toll plaza, at the end of a 2,130-foot inclined ramp which forms a spiral bridge, going through a full 360-degree loop while gaining elevation over land to provide almost 200 feet of clearance over the shipping channel. The north end connects directly to SR 401 at an at-grade intersection. Since most of the northern portion of the bridge is over shallow, non-navigable water, it is low to the water.

(Astoria-Megler Bridge from the South ramp.)

Shown below in the next several pictures, we are crossing this long bridge from the Washington side to the Oregon side.

As you can see in the picture above, we have now entered Oregon.

We continued on until we were across the bridge.

Exiting the bridge, we can now see Astoria, Oregon ahead.

We are now heading down by the port area of Astoria.

(Shown above is the Port of Astoria, Oregon.)

Astoria is a port city and the seat of Clatsop County, Oregon, with a population of 10,181. Founded in 1811, Astoria is the oldest city in the state and was the first permanent American settlement west of the Rocky Mountains. The county is the northwest corner of Oregon, and Astoria is located on the south shore of the Columbia River, where the river flows into the Pacific Ocean. The city is named for John Jacob Astor, an investor and entrepreneur from New York City, whose American Fur Company founded Fort Astoria at the site and established a monopoly in the fur trade in the early 19th century. Astoria was incorporated by the Oregon Legislative Assembly on October 20, 1856.

(Shown above is a sketch of Astoria, Oregon, the entrance to the Columbia River in 1882.)

During archeological excavations in Astoria and Fort Clatsop in 2012, trading items from American settlers with Native Americans were found, including Austrian glass beads and falconry bells. The present area of Astoria belonged to a large, prehistoric Native American trade system of the Columbia Plateau.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition spent the winter of 1805–1806 at Fort Clatsop, a small log structure southwest of modern-day Astoria. The expedition had hoped a ship would come by that could take them back east, but instead, they endured a torturous winter of rain and cold. They later returned overland and by internal rivers, the way they had traveled west. Today, the fort has been recreated and is part of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park.

(Shown above is Fort Astoria, ca 1813.)

In 1811, British explorer David Thompson, the first person known to have navigated the entire length of the Columbia River, reached the partially constructed Fort Astoria near the mouth of the river. He arrived two months after the Pacific Fur Company's ship, the Tonquin. The fort constructed by the Tonquin party established Astoria as a U.S., rather than a British settlement and became a vital post for American exploration of the continent. It was later used as an American claim in the Oregon boundary dispute with European nations.

The Pacific Fur Company, a subsidiary of John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company, was created to begin fur trading in the Oregon Country. During the War of 1812 in the year 1813, the company's officers sold its assets to their Canadian rivals, the North West Company, which renamed the site Fort George. The fur trade remained under British control until U.S. pioneers following the Oregon Trail began filtering into the town in the mid-1840s. The Treaty of 1818 established joint U.S. – British occupancy of the Oregon Country.

In 1846, the Oregon Treaty divided the mainland at the 49th parallel north, making Astoria officially part of the United States. As the Oregon Territory grew and became increasingly more colonized by Americans, Astoria likewise grew as a port city near the mouth of the great river that provided the easiest access to the interior. The first U.S. post office west of the Rocky Mountains was established in Astoria in 1847 and official state incorporation in 1876.

In 1883, and again in 1922, downtown Astoria was devastated by fire, partly because the buildings were constructed mostly of wood, a readily available material. The buildings were entirely raised off the marshy ground on wooden pilings. Even after the first fire, the same building format was used. In the second fire, flames spread quickly again, and the collapsing streets took out the water system. Frantic citizens resorted to dynamite, blowing up entire buildings to create fire stops.

We got another look at the Astoria-Megler Bridge while we were in Astoria.

Leaving Astoria, we continued on US Hwy 101 South toward Seaside.

It is raining again. Now Seaside is 15 miles away, Tillamook is 60 miles away, and Newport is 133 miles away.

We are now crossing the bridge over Youngs Bay into Warrenton, Oregon.

The New Youngs Bay Bridge is a vertical-lift bridge over Youngs Bay on US Hwy 101 between Astoria and Warrenton. Including the approaches, it is 4,200 feet long and was completed in 1964. The road bridge had been proposed since 1948 and was approved by the state government in the late 1950s. The routing across Youngs Bay for US Hwy 101 was chosen in 1955 over a more inland alignment that would have avoided the bay entirely. Construction began in March 1963 and was dedicated on August 29, 1964.

The bridge was built to the west of andclosely in parallel to a 1.6-mile railroad trestle which also crossed the bay. It was built in 1896 for the Astoria and Columbia River Railway Company. The New Youngs Bay Bridge passed over the top of the railway bridge near the north river bank. The railroad bridge was used for the last time in 1982 and was dismantled in 1986.

Shown above is the vertical lift section of the New Youngs Bay Bridge, a 1964-built bridge over Youngs Bay on US Hwy 101.

We are now in Warrenton, Oregon. Warrenton is a small, coastal city in Clatsop County, Oregon, with a population of 6,277. Named for Daniel Knight Warren, an early settler, the town is primarily a fishing and logging community.

Prior to the arrival of the first settlers, this land was inhabited by the Clatsop tribe of Native Americans, whose tribe spanned from the south shore of the Columbia River to Tillamook Head. The county in which Warrenton is located was named after these people, as well as the last encampment that the Lewis and Clark Expedition established. Today, a replica of Fort Clatsop still stands just outside of Warrenton city limits.

(Shown above is the historic D.K. Warren House, that was built in 1885.)

The first settlement within Warrenton city limits was Lexington, which was laid out in 1848, and served as the first county seat for Clatsop County. The name fell out of use for a time, and the area became known as Skipanon – a name that is now preserved by the Skipanon River, which flows through the town. A Lexington post office operated intermittently between 1850 and 1857; a Skipanon post office operated continuously from 1871 to 1903.

In 1863, the military battery, Fort Stevens, was built in the Warrenton area near the mouth of the Columbia River. Though military activity ceased in 1947, the remains of the fort are preserved as part of Fort Stevens.

Very few improvements were made to the land until the early 1870s, when D. K. Warren bought out some of the first settlers. With the help of Chinese labor, Warren reclaimed a large tract of the land by constructing a dike about 2.5 miles in length, which was completed in 1878. Warren laid out the town in about 1891, and in the following year built the first schoolhouse, at a cost of $1,100, and gave it to the school district. Warrenton was platted in 1889 and incorporated as a city in 1899. Built on tidal flats, it relied on a system of dikes built by Chinese laborers to keep the Columbia River from flooding the town.

We drove by Fort Clapsop and Fort Stevens State Park.

As it continued to rain steadily, we drove past Lewis & Clark National Historical Park.

We drove by Sunset Beach Trailhead and Fort to Sea Trail, which were both off to the right. The Fort To Sea Trail starts in the woods south of Fort Clatsop and goes to Sunset Beach on the Pacific Ocean, winding through ancestral lands of the Clatsop Indians who aided the Corps during their 1805/1806 winter stay at the Pacific.

We then drove by the Cullaby Lake County Park, Carnahan County Park, and the Historic Lindren House. The historic Lindgren cabin located in Cullaby lake park south of Astoria was built by Eric Lindgren, a Swedish Finn in the 1920s. He constructed it with huge, old-growth red cedar and all the logs were hewn by hand with a broadaxe to a 6" thickness (see below)!

We next drove into Seaside, Oregon. Seaside is a city in Clatsop County, Oregon on the coast of the Pacific Ocean, with a populatiob of 6,457. The name Seaside is derived from Seaside House, a historic summer resort built in the 1870s by railroad magnate Ben Holladay.

The Clatsop were a historic Native American tribe that had a village named Ne-co-tat (in their Chinook language) in this area. Indigenous peoples had long inhabited the coastal area. About January 1, 1806, a group of men from the Lewis and Clark Expedition built a salt-making cairn at the site later developed as Seaside. Seaside was not incorporated until February 17, 1899, when coastal resort areas were being settled.

(The Gilbert House in Seaside, Oregon.)

In 1912, Alexandre Gilbert (1843–1932) was elected Mayor of Seaside. Gilbert was a French immigrant, a veteran of the Franco Prussian War (1870-1871). After living in San Francisco, California and Astoria, Oregon, Gilbert moved to Seaside where he had a beach cottage (built in 1885). Gilbert was a real estate developer who donated land to the City of Seaside for its one-and-a-half-mile-long Promenade, or "Prom," along the Pacific beach.

In 1892, he added to his beach cottage. Nearly 100 years later, what was known as the Gilbert House was operated commercially as the Gilbert Inn since the mid-1980s. Both it and Gilbert's eponymous "Gilbert Block" office building on Broadway still survive. Gilbert died at home in Seaside.

Tillamook is now 48 miles away.

Continuing on US Hwy 101 South, we passed the junction for US Hwy 26 East to Portland.

We are soon at Cannon Beach. Cannon Beach is a small coastal city in northwest Oregon. It’s known for its long, sandy shore. Cannon Beach has a population of 1,690, and is a popular coastal Oregon tourist destination, famous for Haystack Rock, a 235 feet sea stack that juts out along the coast.

(An aerial view of Cannon Beach with Haystack Rock in the background.)

Cannon Beach and its surrounding coast was previously settled by the Tillamook people. William Clark, one of the leaders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, journeyed to Cannon Beach in early 1805. The expedition was wintering at Fort Clatsop, roughly 20 miles to the north near the mouth of the Columbia River. In December 1805, two members of the expedition returned to camp with blubber from a whale that had beached several miles south, near the mouth of Ecola Creek. Clark later explored the region himself. From a spot near the western cliffs of the headland Clark said he saw ". . . the grandest and most pleasing prospects which his eyes had ever surveyed, in front of a boundless Ocean . . ." That viewpoint, later dubbed "Clark's Point of View," can be accessed by a trail from Indian Beach in Ecola State Park.

(Shown above is Haystack Rock during low tide.)

Clark and several of his companions, including Sacagawea, completed a three-day journey on January 10, 1806, to the site of the beached whale. They encountered a group of Tillamook who were boiling blubber for storage. Clark and his party met with them and successfully bartered for 300 pounds of blubber and some whale oil before returning to Fort Clatsop. There is a whale sculpture commemorating the encounter between Clark's group and the Tillamooks in a small park at the northern end of Hemlock Street.

Clark applied the name Ekoli to what is now Ecola Creek. Ehkoli is a Chinook word for "whale". Early settlers later renamed the creek "Elk Creek", and a community with the same name formed nearby.

(Every June, Cannon Beach hosts an annual sand castle–building contest.)

In 1846, a carronade, a short naval cannon, from the US Navy schooner Shark, which had sunk earlier that year, washed ashore just north of Arch Cape, a few miles south of the community. The schooner hit land while attempting to cross the Columbia Bar, also known as the "Graveyard of the Pacific." The cannon, rediscovered in 1898, eventually inspired a name change for the growing community. In 1922, Elk Creek was renamed Cannon Beach (reflecting the 8-mile beach that extends south of Ecola Creek to Arch Cape) at the insistence of the Post Office Department because the name was frequently confused with Eola. Elk Creek itself was renamed Ecola Creek to honor William Clark's original name.

US Hwy 101 formerly ran through Cannon Beach. In 1964, a tsunami generated by the Good Friday earthquake came ashore along the coast of the Pacific Northwest. The subsequent flooding inundated parts of Cannon Beach and washed away the highway bridge located on the north side of city. Cannon Beach, now isolated from the highway, decided to attract visitors by holding an annual sand castle contest in June.

We next crossed the Arch Cape Creek Bridge that was built in 1932. The Arch Cape Creek Bridge abutted up to the Arch Cape Creek Tunnel. The Arch Cape Creek Tunnel is an arched tunnel that is 14 feet high in its middle, but drops to under 12 feet at the tunnel’s sides and is 1,227 feet long (see below).

(Shown above is a historical photograph of the south entrance to Arch Cape Tunnel, ca July 3, 1944.)

We then passed the Oswalt West State Park.

Tillamook is now 27 miles away.

We continued to follow US Hwy 101 South to Tillamook.

Tillamook is now 23 miles away.

We passed the sign for Port of Garibaldi. The Port of Garibaldi is the closest seaport to Portland, Oregon and was established in 1910.

We then drove under this unique looking bridge (see above).

Tillamook is now 14 miles away.

Looking ahead, we can see a tall gray tower. I wonder what it is? (See pictures above and below of the tower.) I later found out that it is a great smokestack that still remains in Garibaldi to this day, that was first built by a man named Hammond in the 1927. The smokestack was part of the Hammond Lumber Company. People from the time period described him as an exceptionally caring and generous man. Hammond built the smokestack to spare the townspeople of Garibaldi from choking on the fumes from his saw mill. Even today, it remains one of the tallest man-made structures along the Oregon coast.

We are now in Garibaldi, which officially became a city in 1946 -- over 75 years after Daniel Bayley was granted a title to the land by President Ulysses S. Grant. Daniel Bayley was one of the first significant property owners at the time. He established a general store and a hotel on the street now known as Bay Lane. The city of Garibaldi has since had its fair share of lumber mills, including the Whitney Mill, the Hammond Lumber Company, Oceanside Lumber Company and Oregon-Washington Plywood Corporation. The Weyerhaeuser Company still operates a hard wood lumber mill in the Port of Garibaldi.

We then drove by the Kilchis River County Campground, located just outside of Tillamook, Oregon.

We have now arrived in Tillamook, Oregon. Tillamook is a town, with a population of 5,231, that is found within a fertile river valley on the southeast edge of the Pacific Ocean, adjacent to Tillamook Bay. Located amidst a tangle of rivers and farm fields, Tillamook is renowned for its agriculture that stewards and cultivates the region’s natural beauty. A highly successful dairy industry has led the name Tillamook to be frequently associated with dairy products, and tours of the sophisticated Tillamook Creamery are one of the most popular attractions in town.

Tillamook is named for the Tillamook people, a Native American tribe speaking a Salishan language who lived in this area until the early 19th century. The Tillamook Native Americans are the southernmost branch of the Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest. This group was separated geographically from the northern branch by tribes of Chinookan peoples who occupied territory between them. The name Tillamook is of Chinook origin, and refers to the people of a locality known as Elim or Kelim. They spoke Tillamook, a combination of two dialects. Tillamook culture differed from that of the northern Coast Salish, and might have been influenced by tribal cultures to the south, in what is now northern California.

Captain Robert Gray first anchored in Tillamook Bay in 1788, marking the first recorded European landing on the Oregon coast. Settlers began arriving in the early 1850s, and Tillamook County was created by the Territorial legislature in 1853. In 1862, the town itself was laid out, and the first post office was opened in 1866. The town was voted to be the county seat in 1873, and Tillamook was officially incorporated as a city in 1891.

During World War II, the United States Navy operated a blimp patrol station near the town at Naval Air Station Tillamook. The station was decommissioned in 1948, and the remaining facility now houses the Tillamook Air Museum.

Historically, the Tillamook economy has been based primarily on dairy farms. The farmland surrounding the city is used for grazing the milk cattle that supply the Tillamook County Creamery Association's production of cheese, particularly cheddar, gourmet ice cream and yogurt, and other dairy products. Approximately one million people visit the Tillamook Creamery Cheese factory each year.

We pulled into a large parking lot where RVs were parking, and then walked up to the Visitor Center. With approximately 1.3 million annual visitors traveling to Tillamook, Oregon to view cheesemakers at work, the cheese factory is truly a tourist attraction. The Tillamook Cheese Factory produces more than 170,000 pounds of cheese each day and packages approximately one million pounds of cheese on-site each week. The factory warehouse has the capacity to age 50 million pounds of cheese at once.

A photo of a cow ten times bigger than life greeted us as we entered the Visitor Center at the Tillamook Cheese factory (see above). Sweet-faced Tillie of Tillamook, a little brown Jersey cow that was used to promote Tillamook Cheese over 50 years, is no longer used as the cow ambassador. Instead, a "no name" cow's picture seems to say to visitors, "On the farm, I make the milk. Here, they make the cheese. Come on in and look around." That's a very welcoming stance for a cow ambassador, even if it's unnamed. Maybe they should call the new cow ambassador Minnie or Winnie the Moo -- I think that would be appropriate!

More than 100 years ago several small creameries joined together to form the Tillamook County Creamery Association, which is still owned today by more than 100 farm families.

Today, the Tillamook Cheese Factory is open for self-guided tours every day of the year, except Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day. Visitors can watch the cheese making process throughglass windows looking down into the plant. Not only are tourists awed by Tillamook's mind-boggling cheese-producing capacity, they're also taken behind the curtain and shown how it's all made possible.

Each year, nearly 1.3 million people pass through the creamery on self-guided tours, witnessing the magic of how Tillamook's impeccable products are formed, processed, and packaged. Tourists even learn about the secret ingredient that gives Tillamook cheddar its distinctive orange hue as they step through the company's history. The self-guided tours of Tillamook Creamery allow you to explore the bounds of their barn-like factory, while taking in Tillamook's epic tale at your own pace within their epic factory, and then having an opportunity to stop for something delicious that's fresh off the line — such as ice cream!

Known to most consumers as a lovable loaf of orange cheddar, the Tillamook brand has made a name for itself as the great Northwest's titan of dairy. A national brand from Oregon, this rich cheese with the ship on the label delivers a flavorful history.

From its humble start as a tiny farming cooperative, the Tillamook brand has served tastes for over 100 years. A company that's proudly filler-free, packing flavor and texture to the savory limits of the human palate. When lesser dairies take shortcuts on quality, Tillamook doubles-down. That's been their directive since day one. A directive that's driven their product to celebrity status in your dairy aisle.

Tillamook's creamy history tells a story of success from very humble beginnings. Beginning in Tillamook County, when a small group of dairy farmers from the dewy valleys of Oregon joined forces in 1909, and soon became a force of their own. Tillamook's top-shelf curd is the product of the Tillamook County Creamery Association. A dairy cooperative that today is the largest employer in Tillamook County, an economic engine empowering nearly 900 people in the craft of fine dairy.

Years of small-time dairy farming offered decent yields, but it wasn't until local dairy farmers formed a cooperative in 1909, when Tillamook truly entered their stride. The Tillamook County Creamery Association's catalyzing event started simply. The inaugural cooperative welcomed 10 independent dairy farmers. All they had to pay was a $10 entry fee, and from there they combined their resources to change cheese-making history.

Today that co-op belongs to 80 farmer-owners, and has propelled the Tillamook County Creamery Association into a top-50 American cheesemaker. Tillamook's commitment to quality and teamwork also shows up in their long-standing record of integrity, as the cooperative has held a constant commitment to stewardship — both to the Tillamook County community and to their customers.

Before the cooperative could take off, the Tillamook County dairy farmers first had to solve their distribution woes. Prior to the advent of refrigerated cars, time was a factor in transporting perishable dairy. And given the obvious lack of freeway infrastructure, the fastest route to Oregon's biggest city, Portland, was via water. So the people of Tillamook County came up with a plan: Build a ship. Specifically, a schooner that was dubbed "The Morning Star."

The ship-build was a success and ironically enough The Morning Star (shown above) became the first ship built in Tillamook County and registered in Oregon. The vessel's name was originally derived from the belief that this ship would dawn a new day upon Tillamook County. A prophecy that held true, as the outline of this iconic vessel serves as the logo Tillamook uses on their offerings today. This ship is such a staple of Tillamook's history, for both the brand and the county, that a full-size replica of the schooner sits on display at the Tillamook Creamery's main factory.

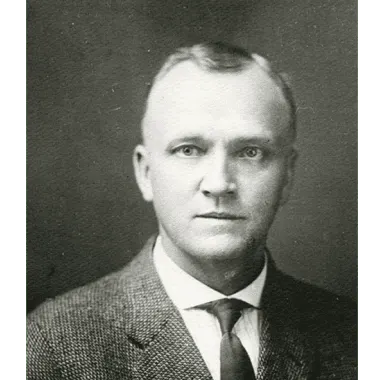

The richly specific taste of Tillamook traces back to a serendipitous partnership with a genius cheese artist. When Canadian cheesemaker Peter McIntosh migrated to Tillamook County, he brought an artisanal arsenal of cheese-crafting knowledge with him, according to Oregon Live. Having operated a dairy factory in Ontario, Canada, McIntosh had consistently refined a promising cheddar formula, and all he needed was a chance to prove his prowess. McIntosh wanted a cheesemaking plant of his own. Luckily for the lactose tolerant, Tillamook gave him that opportunity.

In 1894, McIntosh was hired to operate Tillamook County's first commercial cheese plant. He taught Tillamook dairy farmers everything he knew, and in 1909, The Tillamook County Dairy Cooperative rewarded McIntosh's ingenuity, incorporating his popular cheesemaking formula as their formulaic standard. A repeatable and winning recipe that is still a part of Tillamook's winning tradition today. And all thanks to "The Cheese King of The Coast" spreading his gospel of cheese throughout the fertile Tillamook valleys.

(Shown above is renowned Canadian cheesemaker Peter McIntosh that brought his cheddar cheese-making expertise to Tillamook County, where he taught the locals all he knew, earning the nickname “Cheese King of the Coast.”)

If Tillamook County dairy farmers were committed enough to build Oregon's first ship, and actually sail it, imagine how great their cheese could be? The world didn't wait long for that answer -- as Tillamook County's first big culinary victory came at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis. Ten years into McIntosh's influence, it showed early proof positive that his formula scaled to success. A harbinger event that paved the way to McIntosh's work and Tillamook's merging as one.

This event also paved the way to Tillamook becoming a full cooperative. As their products continued to improve and expand, working together with other dairy farmers became both lucrative and essential. McIntosh's cheese-making methods would continue to dominate the competition, and Tillamook County would continue to expand it's dairy-making success. The 1904 World's Fair was a huge victory — but Tillamook County wasn't done yet.

Cheese does not get taken lightly in Wisconsin, a state where cheese is major-league. Cooking a cheese curd wrong could get you ostracized. So for all intents and purposes, if your cheese can win here, it can win anywhere. And that's what Tillamook did. Having established themselves in the American Northwest as committed to quality, it was only a matter of time before Tillamook's premium product won recognition in America's Dairyland. In 2010, their mild cheddar obliterated the competition, scoring 99.6 out of 100 points at the World Cheese Championship in Wisconsin. Not only did Tillamook wrest the championship belt from the cheese-obsessed Midwest, their mild-cheddar variety bested all 59 competitors in the category. Far from a mild showing by a cheese that excelled to just four-tenths of a point shy of perfection.

The first thing we did was head upstairs to take in the free self-guided tour of the cheese factory (see picture above of Mel climbing the stairs). When you are up above the plant, you can watch the cheese being processed and packaged by the workers below. It’s amazing the quantity of cheese made every day. There are signs and displays depicting the early days of the factory and explaining the processes involved in cheese making. Around 1.7 million gallons of milk are received into the factory each day -- yielding 187,000 pounds of cheese each day!

(Shown above is the self-guided tour area at the Tillamook Creamery.)

It was fun to watch the workers on the assembly line performing their different tasks from breaking the cheese into the blocks to laying it out on the conveyor belts, and then inspecting the final product.

(Shown above are the cooking vats at the Tillamook Creamery.)

So here's how the cheese-making process begins -- starting at the cooking vats. Each vat is eight feet high and filled with milk from the bottom. It takes 70 minutes for each vat to fill and the curd to set. Then it takes 40 minutes for the cooked curds to move on to the next step in the process. Each vat produces three to four batches of curds every day.

(Shown above and below are the cooking vats.)

(The cheddarmaster at the Tillamook Creamery.)

And the whey that comes out of the curds isn’t wasted. It’s turned into a sweet whey powder that’s used in high-protein drinks, baby formula, protein bars, and other products. Then the curd mats move to the salter. Salt is the only ingredient added to the Tillamook cheese. As the salt draws out more whey, it slows the production of lactic acid. Less whey makes the cheese drier, which helps in the aging process. From there, the curd mats are compressed into 40-pound blocks in the block-forming towers and then vacuum sealed.

(Shown above is a block-forming tower on the left and a vacuum sealer on the right at the Tillamook Creamery.)

The storyboard above told us about what goes on inside the blockforming towers. Each tower holds 800 pounds of curds -- putting 800 pounds of pressure on the bottom layer. A guillotine cuts off the bottom of the column, forming a 40-pound block. A pusher cylinder pushes the block into the bag. Every two minutes, the whole process repeats! A value opens an the next 40 pounds of curds gets pulled into the top of the tower.

(Shown above are some of the 40-pound blocks of cheese.)

The tour included signage (see above) that explained what you saw, plus cheese-making factoids. It is interesting that the curds after being pressed for approximately 30 minutes -- voila, become a block of cheese. Who knew that a “forty” was a cheese block weighing between 41 and 42 pounds?

(Shown above is the journey to the cold storage warehouse at the Tillamook Creamery.)

It is then that the blocks move to the cold storage warehouse to age. When the cheese has finished aging, the blocks are quality tested for smell, texture, and taste. Some might return to the warehouse for further aging, and the rest goes to the cutting machine to be cut into smaller blocks that will be shipped to supermarkets.

(Shown above is the quality checkpoint at the Tillamook Creamery.)

(Shown above is cutting of the cheese into smaller blocks at the Tillamook Creamery.)

(Shown above is the inspecting of the smaller blocks of cheese at the Tillamook Creamery.)

Next, after the blocks of cheese pass inspection, they are moved to the Blue Octopus vacuum sealer. The machine got its name from its movement, which looks like a ride at an amusement park. Each chamber closes over a block of cheese and shrink wraps the cheese.

(Shown above is the Blue Octopus shrink wrapper at the Tillamook Creamery.)

Next, after the vacuum sealer gives each package an airtight seal, a spinning arm pushes each package onto a conveyor belt that runs through a heat-shrink tunnel. Steam heat shrinks the bag around the cheese, smoothing away any rough edges.

Next, some of the cheese blocks are then cut into smaller blocks and sent to the patching station where the cheese is weighed for consistency.

(Shown above the cheese is being cut, weighed, and patched to make just the right size blocks.)

(Shown above are blocks that aren’t the perfect weight as they get shifted to the side.)

(Shown above is where slices get added to blocks that are too light before heading back down the line.)

(Shown above is the cheese cutter in action.)

The storyboard above told us how the inside of the cutter works with it taut sharp wires. The first push-plate pushes the cheese block through the vertical wires along the long side into fifths. A second push-plate pushes the cheese through the wires the other way into fourths.

Lastly, the final step of the process is when the packaged cheese is ready to be boxed and shipped to market.

After our self-guided factory tour, we headed downstairs and got in line for some free pre-wrapped cheese samples -- Colby Jack, Sharp, Medium and White Cheddar. We grabbed one or two samples of each type. Since Tillamook Cheese is world-famous for their great tasting cheddar and they had many types available for tasting and also for sale.

(Shown above are some of the free samples of Tillamook cheese available at the end of the tour. My favorite was the Colby Jack Cheese.)

We then walked over to the Tillamook Creamery Store to take a look. There they sold cheese, as well as all kinds of Tillamook Cheese branded merchandise, local Oregon Coast jams, coffee, mustard, sauces, candy, fudge and on and on.

(Shown above is a view of the Tillamook Creamery store from the second floor.)

(Shown above is a view of the inside of the Tillamook Creamery store.)

(Shown above is just a glimpse of some of the fresh cheese for sale at the Tillamook Creamery store.)

And if you want, you can also buy a cup of Tillamook ice cream or get yourself a nice scoop of fresh Tillamook ice cream in a made-on-site waffle cone. A sign showing some of the many Tillamook ice cream flavors is shown below.

We didn't get a chance to buy any because the line for ice cream was so long (see below).

(Shown above and below is the Tillamook Cheese Van on display across the hall from the store.)

Lastly, before leaving we took a look at the Tillamook Cheese Factory "Baby Loaf" mini Volkswagon van that was used as the Tillamook Cheese promotional vehicle. In the summer of 2010, the "Love Loaf Tour" hit over 100 U.S. cities in a fleet of cheddar-orange Volkswagen mini buses that crisscrossed the country in a motorized facsimile of Tillamook's "Baby Loaf" variety of cheddar. Since Tillamook sells their cheese in what they call a loaf, this was a great, cheesy tourist photo-op!

After leaving the Tillamook Creamery, we continued our travels, and it once again started raining as we crossed a bridge.

Soon we drove past the turnoff for Cape Meares and the Three Capes Scenic Route. We stayed on US Hwy 101, heading toward South Beach, Oregon.

We turned right following US Hwy 101 to Lincoln City, Oregon.

We continued on toward Newport, Oregon, which is 45 miles away.

We then drive by Neskowin Beach.

(Shown above is the entrance to Neskowin Beach State Park.)

We then drove by the Chinook Winds Casino turnoff. We will go to this casino another day while we are in South Beach, Oregon.

Next, we passed the Devils Lake turnoff. Devils Lake is a small lake in Lincoln County, Oregon along the Oregon Coast. It separates the northern part of Lincoln City from the Central Oregon Coast Range. It is 1/3 of a mile wide, three miles long, and up to 21 feet deep. The D River flows from the lake westward to the Pacific Ocean. At 120 feet, it is one of the world's shortest rivers, but for a definition of river that excludes estuaries. According to Oregon Geographic Names, the name derives from a Native American legend. In the legend, a giant fish, giant octopus, or other large marine creature would occasionally surface, much to the dismay of anyone fishing in the vicinity.

(Devils Lake from above the Pacific Ocean.)

We are now in Lincoln City, Oregon, located on the Oregon Coast between Tillamook and Newport. It is named after the county, which was named in honor of former U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. The town has a population of 9,815. Lincoln City was incorporated on March 3, 1965, uniting the cities of Delake, Oceanlake and Taft, and the unincorporated communities of Cutler City and Nelscott. These were adjacent communities along U.S. Route 101, which serves as Lincoln City's main street. The name "Lincoln City" was chosen from contest entries submitted by local school children. The contest was held when it was determined that using one of the five communities' names would be too controversial.

We continued our coastal drive along US Hwy 101.

We drove by Beverly Beach State Park. Beverly Beach State Park is a state park in Oregon located 5 miles north of Newport.

The Pacific Ocean is really rough today as we drive along the coast of US Hwy 101.

We drove by Moolack Beach, an undeveloped sandy beach on the Oregon Coast about 4 miles north of Newport in Lincoln County. It is almost 5 miles in length with the south end at Yaquina Head and the north end at Otter Rock, the site of Devils Punch Bowl State Natural Area. The northern beach is the site of Beverly Beach State Park and the community of Beverly Beach. The beach has no obvious break delineating what would seem to be Beverly Beach, though Wade Creek is a likely candidate. The nearly ten-foot tidal range and seasonally varying slope of the beach can cause the sandy beach to completely disappear at times; at other times it can be hundreds of feet wide. The beach is bounded by U.S. Route 101. The name is from a Chinook Jargon word for "elk".

We are now in Newport, Oregon. Newport is a city in Lincoln County, Oregon, that was incorporated in 1882, though the name dates back to the establishment of a post office in 1868. Newport was named for Newport, Rhode Island and has a population of 10,853. The area was originally home to the Yacona tribe, whose history can be traced back at least 3000 years. White settlers began homesteading the area in 1864. The town was named by Sam Case, who also became the first postmaster.

Newport has been the county seat of Lincoln County since 1952, when voters approved a measure to move the center of government from nearby Toledo to Newport. It is also home of the Oregon Coast Aquarium, Hatfield Marine Science Center, Nye Beach, Yaquina Head Light, Yaquina Bay Light, Newport Sea Lion Docks, Pacific Maritime Heritage Center, and Rogue Ales. The city is the western terminus of U.S. Route 20, a cross-country highway that originates in Boston and is the longest road in the United States.

We crossed over the Yaquina Bay Bridge on US Hwy 101. The Yaquina Bay Bridge is an arch bridge that spans Yaquina Bay south of Newport, Oregon. It is one of the most recognizable of the US Hwy 101 bridges designed by Conde McCullough and one of eleven major bridges on the Oregon Coast Highway designed by him. It superseded the last ferry crossing on the highway. Work on the Yaquina Bay Bridge began on August 1, 1934. The bridge opened on September 6, 1936, at a cost of $1,301,016 ($27,440,000 in today's dollars). A total of 220 people worked to pour 30,000 cubic yards of concrete and fabricate 3,100 tons of steel. The contractors were the Gilpin Construction Company of Portland, Oregon, and the General Construction Company of Seattle, Washington. The main arch was built in toward the center from the anchorages, using tiebacks to support the arch until it could be closed. The piers are supported by timber pilings driven to a depth of about 70 feet below sea level.

The 600-foot main span is a semi-through arch, with the roadway penetrating the middle of the arch. It is flanked by identical 350-foot steel deck arches, with five concrete deck arches of diminishing size extending to the south landing. The main arch is marked by tall obelisk-like concrete finials on the main piers, with smaller decorative elements marking the ends of the flanking spans. The arches are built as box girders. The two-lane road is 27 feet wide, running inside the arches with two 3.5-foot sidewalks. The main arch is 246 feet above sea level at its crown. Overall length of the bridge is 3,260 feet, including concrete deck-girder approach spans. The navigable channel measures 400 feet wide by 133 feet high.

The bridge uses Art Deco and Art Moderne design motifs as well as forms borrowed from Gothic architecture. The Gothic influence is seen in the balustrade, which features small pointed arches, and in the arches of the side span piers. The ends of the bridge are augmented by pedestrian plazas that afford a view of the bridge and provide access to the parks at the landings by stairways.

(Shown above is the Port of Newport and Yaquina Bay Bridge on US Hwy 101.)

We drove by the turnoff for the Oregon Coast Aquarium and the OSU Hatfield Marine Science Center.

Next we drove by the South Beach State Park. Situated next to the Yaquina Bay Bridge, South Beach State Park begins in south Newport and stretches several miles down the Oregon coast. This historic park offers access to miles of broad, sandy ocean beach and trails for walking and bicycling.

We arrived at Whalers Rest Thousand Trails Campground in South Beach, Oregon at 2:30 p.m. Whalers Rest Thousand Trails Campground is located on the Oregon Coast, just 150 yards from the Pacific Ocean. We camped on site #12 for 7 nights.

South Beach is an unincorporated community in Lincoln County, Oregon, located along the Pacific coast at Yaquina Bay, 1.5 miles south of Newport.

For dinner tonight, we had leftover chili and a fried egg and cheese sandwich.

Tuesday, September 26, 2023

This morning started out rainy at 58 degrees, which would turn sunny by the afternoon reaching 63 degrees. After a breakfast of waffles and bacon, Mel went for a walk around the campgound and down to the beach. I worked on my blog.

Around 11:30 a.m., we decided to run some errands in Newport.

We crossed the Yaquina Bay Bridge again.

Shown above is a picture taken from the Yaquina Bay Bridge.

Our first stop was at the Circle K in Newport where we stopped to get gas. Next, we stopped at Fred Meyers to get some groceries. And then our last stop in Newport was at the Quilter's Cove. Here I bought the 2023 row by row quilt pattern kit, and received two free patterns as well.

Shown above and below is what the inside of Quilter's Cove looked like.

We have truly enjoyed a wonderful drive along US Highway 101 and the beautiful coast of Oregon the last couple days!

Shirley & Mel

.jpg)

.jpg)

_ASTORIA,_OREGON,_ENTRANCE_TO_COLUMBIA_RIVER.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment