This morning, it was cloudy with a temperature of 53 degrees, but it soon became sunny. It's a relief to have it not be raining.

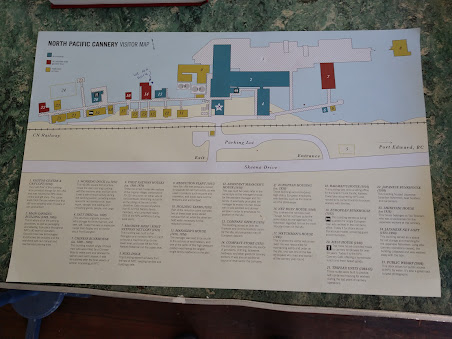

We left the campground this morning at 10:15 a.m. and headed to the North Pacific Cannery National Historic Site located near Port Edward to take a tour.

The North Pacific Cannery National Historic Site of Canada was a late 19th century, early 20th century salmon cannery complex, located in the community of Port Edward, just south of the city of Prince Rupert on the northwest coast of British Columbia. The cannery complex was situated on a narrow strip of land between the mountains and the Inverness Passage, at the mouth of the Skeena River on "Cannery Row."

The cannery had to be near the fishing grounds since the area was remote and without refrigerated boats, the catch had to be transported quickly to a processing plant. In addition, there was also a relatively large First Nation population with salmon fishing expertise there.

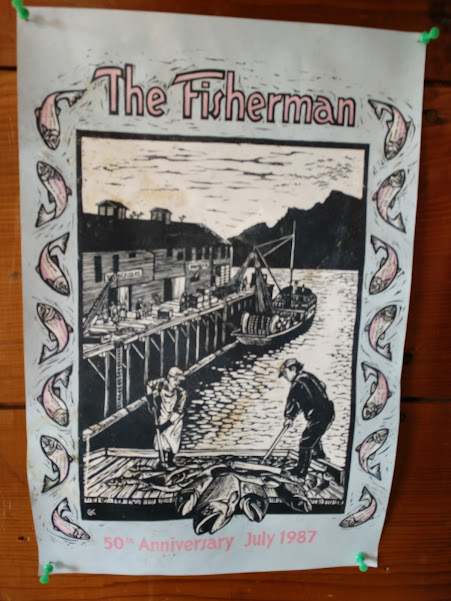

The North Pacific Cannery is comprised of a cluster of wooden buildings, mostly one-story in height, grouped along a wooden boardwalk. The boardwalk and many of the buildings are supported on pilings over the water. The site is now operated as a cannery museum. The North Pacific Cannery National Historic Site showcases the history of the fishing industry and the role of canneries in the area. It was the last remaining cannery village on North America’s West Coast. The plant stopped processing salmon in 1968, becoming a reduction plant until its closure in 1981 after 80 years of operations.

We went on a private guided tours (for $12 CA/senior -- or $8.76 US/senior). From the tour, we learned that nearly 1,000 people once lived and worked at the North Pacific Cannery.

The North Pacific Cannery was founded in 1889 by Angus Rutherford Johnston, John Alexander Carthew, and Alexander Gilmore McCandless, as a village where the European bosses presided over segregated communities of Chinese, Japanese and First Nations workers. The 183 acres of land was purchased for $32 by Carthew.

John Carthew sold it to Henry Ogle Bell-Irving in 1891. However shortly after it was built in 1891, heavy rains caused a mud slide that wiped out the cabins used by the First Nation workers and their families. In 1892, when Anglo-British Columbia Packing Company (ABC) purchased the plant, it was a one-line cannery with two rooms for mild cure fish.

A cold storage plant was added in 1910, but it closed in 1920 and was dismantled in 1954. A can-making factory was built at the site in 1918 and until 1936 it supplied cans for Seymour Inlet, Good Hope, British American, Cassiar, Knight Inlet, Arrandale, and Port Nelson canneries. By 1923 the cannery had expanded to a 26,000 square foot, two line operation, with cold storage and a blacksmith shop.

Anglo-British Columbia (ABC) Packing Company operated the plant until the company folded and its assets were sold off. The last full season of salmon canning at North Pacific Cannery was 1968. This ownership history is noteworthy because of its almost continuous ownership by a single firm for over 76 years. This is unusual in an industry marked by acquisitions, mergers, bankruptcies and restructuring.

It was purchased by the Canadian Fishing Company (Canfisco of Vancouver BC) in 1968. The Canadian Fishing Company reopened the plant for a partial season in 1972 after a fire destroyed their Prince Rupert Oceanside plant. BC Packers bought North Pacific Cannery in 1980 and closed it in 1981. It was given a National Historic Site designation in 1985 and now operates as a museum.

Using the map of the North Pacific Cannery, we started at the Visitor Center & Can Loft Area (ca 1918 -- as seen in the picture below).

The Visitor Center was once the Salt Shed (a packing and storage building, ca 1900). It is a gable-roofed building with plywood sheathing, and a convex bowed floor that was built to provide additional storage space for tinned salmon, and was later used for salt storage. The gable-roofed structure with its plywood sheathing is similar to that found on the Main Cannery Building.

We toured the Visitor Center on our own while we were waiting for our tour to begin at 11:00 a.m. The main floor of this building once provided for fish offal and now houses the North Pacific Cannery Visitor Center and Gift Shop. The upper level holds the can reform line that still runs smoothly after 75 years of can production. We also watched a movie while we were in the Visitor Center about the cannery's history.

In order for the North Coast Marine Museum Society to preserve North Pacific Cannery, it had to receive funds up to $4 million -- which was succeeded by the canneries 100th anniversary in 1989.

In the early days, all of the labor was done by hand, from netting the salmon to cleaning and butchering, to can-making, and then to canning. As the 20th century progressed, advances in canning technology would be introduced to save time and work. Early examples of cannery technology at North Pacific include the gang knife and the can soldering machine.

As technology changed, so did the appearance of the Cannery. Mechanization of the canning process made the Chinese tinsmiths’ jobs obsolete, followed by those of the butchers as the Iron Butcher grew in popularity. These machines greatly increased the efficiency of production and saved a good deal of hard labor. This made the Cannery more profitable, but of course resulted in the loss of many jobs.

The North Pacific Cannery has 25 different buildings that we could tour -- including the visitor center, canning loft, First Nation and Japanese Bunkhouses, European house, and the Mess House (which has been turned into a small café).

The memorial (shown above ) at the North Pacific Cannery told us how salmon canning stimulated the economic development on this coast. North Pacific is the oldest West Coast cannery still standing. From here the Bell-Irving family shipped high quality salmon directly to England before 1900. Typical of most canneries in its isolation and operations, North Pacific relied more on native labor than those close to urban centers, was slower to adopt to new technology, and had lower production costs. Ethnically-segregated living and work areas divided Chinese, Indian, Japanese, and white labor. The main cannery structure completed in 1895, remains essentially unaltered.

We met our tour guide at 11:00 a.m. and began our walk. As we strolled along the boardwalk, our tour guide told us important facts about the cannery and its workers. We peered into wooden, tin-roofed homes and stores once used by the families that worked here. Fishing and canning equipment occupied the Main Cannery Building (built in 1889) and is the oldest surviving cannery building in British Columbia. The complex was the site of numerous activities including: a salmon cannery (1890s-1950s); a cure plant (1890s-1920); a can-making factory (post-World War I); a cold storage plant (1900-54); a free oil production plant (early 1950s); and a herring reduction plant (1955-68; and 1972-80).

The layout and built resources of the complex, including a power plant, provisions storage, and workers’ housing, reflect its initial isolation and consequent self-sufficiency, both typical of northern coastal canneries. The design and layout of workers’ housing reflects the multicultural workforce and the ethnic segregation in living and work areas.

The Company Store (circa 1939) was stocked boxes of White Owl cigars, cans of insect spray, bottles of Kik Cola and tube radios. The Mess House – now the Cannery Café – served delicious salmon chowder and homemade baked goods.

Before we went into the Machine Shop/First Nation Net Loft (shown above), we first took a look at the First Nation Houses (shown below).

The First Nation Houses (ca 1900-1970, shown above and below) are two small houses that are replicas of the original village. The original village was comprised of 70 to 120 structures on either side of the boardwalk, stretching out as far as the pilings at the end of the shoreline. Each housed anywhere from 6 to 12 First Nation family members -- who comprised nearly 75% of the North Pacific Cannery workforce during peak years.

First Nation dwellings occupied much of the western portion of the site for much of the period of the Cannery’s operations. These dwellings were simple gable roofed structures, sided with vertical boards and battens, and divided into two rooms. First Nation families lived in these dwellings throughout the fishing season, as men worked on the fishing crews, and women were employed in making and mending nets, as well as looking after their children.

We got a chance to look inside the First Nation dwellings. They looked quite small inside considering that they housed at least six First Nation family members (see pictures above and below).

Shown above is Mel in one of the First Nation dwelling rooms.

The Fuel Dock (shown above and below with the small building) is where they stored the fuel safely away from the rest of North Pacific Cannery.

Next, we walked to the Machine Shop/First Nation Net Loft building (shown below).

On the boardwalk above, Mel and our tour guide visit before entering the Machine Shop/First Nation Net Loft building. The building was built in Port Essington in 1923 and moved to North Pacific Cannery in 1937 to house a machine shop on the lower level, and a net loft in the attic story for the First Nation fishermen to store and mend nets.

The next few pictures (above and below) show the different tools and machines used in the Machine Shop at the North Pacific Cannery.

Next on our tour, we went up to the upper level to look at the Net Loft. The First Nation Net Loft showed the amazing craftmanship that went into the hand-knotted nets used to catch the fish. The netloft area retains the stringers from which nets were suspended during the Cannery’s operation, while the mechanical equipment of the machine shop, including engine, flywheel, pulleys, and lathes, remain largely intact.

Behind one of the doors was a separate area used to store bluestone (or copper sulphate) that was used for cleaning the linen nets. Among the physical values of this building are its board and batten exterior, which impart a distinctive visual character, and its open interior, in which the roof structure is clearly visible.

Above and below is the fishing net untangle and repair room in the Net Loft at the North Pacific Cannery.

Shown below, our tour guide explains the process that was used to prevent rot in the natural fiber nets by using the bluestone tank. She told us the nets were soaked in a bacteria-killing mixture of bluestone (copper sulfate) and water.

Because the workers lived on site during the months of the year the cannery was in operation, their children often lived on site too. The warehouse where the nets were cleaned, dried and repaired also served as a playground for them (see above).

Next, we walked out of the Net Loft down to the Working Dock (ca 1890). This 40,000 square foot structure is one of the largest structures at North Pacific Cannery. It is made up of many pilings driven deep into the river bed that support the wide, open deck. The Working Dock visually and structurally links the Cannery with the water, and protects the Main Canning Building from the impacts of water-borne debris, while also linking with the Machine Shop and Fuel Dock.

In addition, the Working Dock (to the south and adjacent to the Main Cannery Building) was one of the original structures on the site, an integral component of the operations of unloading and distributing fish from boats for processing at the Cannery. It has been added to and rebuilt regularly throughout the evolution of the site. It was a site of much activity during the canning season, providing ample space for net maintenance, boat repair, storage, and loading and unloading goods, people, and cargo (see above).

It also provided a wharf for coastal steamers which unloaded supplies and loaded canned salmon destined for southern markets. It represents the infrastructure needed to operate a north coastal Cannery dependent on water transport for importing provisions and materials, and exporting fish products. During the winter, many boats were stored on the deck. Additional decking was added to the west in 1937, improving the wharf facilities for the steamships. Integral features of the deck include the boat lift, which was used in winching gillnet boats up to the deck level to enable their contents to be off loaded.

Unfortunately, much of the Working Dock structure has deteriorated, prompting a large restoration project. This is a priority structure to be repaired due to its important historical value and also because of its potential as a community gathering space.

Our tour guide told us that many weddings and receptions are held out here on the Working Dock.

It's easy to see why this would make a lovely wedding reception venue.

The canning process began at the unloading dock. In the early years a crew of men called pitchers stood knee-deep in salmon and unloaded the fish from the boats or a fish scow onto the open docks. Fish were moved one at a time with a long handled, one-tined fork called a peugh or pike. The unloading process was mechanized in the 1930s with the introduction of the fish elevator which cut labor costs and preserved quality.

(Standing knee-deep in fish, this worker uses a peugh to unload salmon from the hold of the fishing boat, ca 1952.)

Next, we went inside the Main Cannery Building (ca 1899-1900). This was a timber-framed building with corrugated iron roofing, a low-pitched gable roof, an open "T-shaped" interior space, and a second-story (used for both can storage and as a net loft), all resting on wooden pilings. This is where all of the canning processes, as well as packaging and labeling, took place throughout North Pacific Cannery's 80 years of operation. We discovered how new technologies transformed the industry and the workforce with the mechanized canning lines.

From the first canning line established at the outset, the Cannery expanded its operations to encompass four canning lines at its peak. A major wing was added in 1910, creating the familiar “L” form which has characterized West Coast canneries, subsequently to be converted to a “T”. The large open spaces in the interior were required to enable the installation of a variety of industrial functions -- including butchering, canning lines and can manufacture. Throughout, the materials were simple and utilitarian, and represent a costconsciousness that was general in the industry.

Following the completion of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway line in 1914 connecting Prince Rupert with the rest of Canada through Winnipeg, a land-based transportation route for canned salmon from northern canneries was opened. Then a cold storage plant was established in this wing to enable fresh fish to be stored in preparation for export to Canadian markets.

EARLY DAYS OF THE NORTH PACIFIC CANNERY

In the early days, all of the labor at the cannery was done by hand, from netting the salmon to cleaning and butchering, to can-making, to canning. As the 20th century progressed, advances in canning technology were introduced to save time and work. Early examples of cannery technology at the North Pacific Cannery included the gang knife and the can soldering machine.

In the real early days of a cannery, the salmon was hand-delivered from the butchering station to a hose-fed wooden trough full of cold water. There it was rinsed, scrubbed and scraped clean, then washed again in second tank. After it was washed, the salmon would be placed in wicker baskets for transport to the next station.

Our tour guide told us about how the salmon was washed and sorted/sized before it was placed on the conveyor belt that led to the cutting blades. The wooden table (shown above) was where the men would remove the head, tails, fins and entails from each salmon as it came into the cannery, dumping the refuse through a hole in the floor onto the beach below (see table below). The salmon was rinsed and then the salmon was cut into equal sized pieces for canning.

Originally done by hand by Chinese men, a machine called the “gang knives” reduced the workforce by automating the cutting. Women then placed each piece of cut fish into a can by hand until canning machines took over. By the 1960s, the canning machines incorporated the gang knives so that only a single woman was required to feed whole cleaned fish into the canner. As the salmon was placed on the conveyor rungs of the gang knives machine, another worker would crank the wheel until it cut the fish into chunks (see below).

The gang knives machine would cut a fish into equal-sized portions, replacing the Chinese butchers that had done the job by hand.

Above shows two workers feeding salmon into the gang knives machine at the cannery. The different spacing of the blades on these two machines corresponds to different sizes of cans: one man is cutting fish for half pound cans, and the other is cutting for one pound cans. Next the chunks of salmon were put into cans (see below).

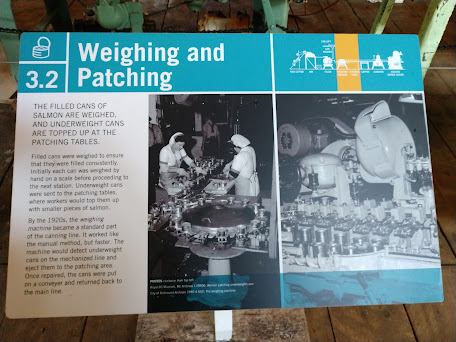

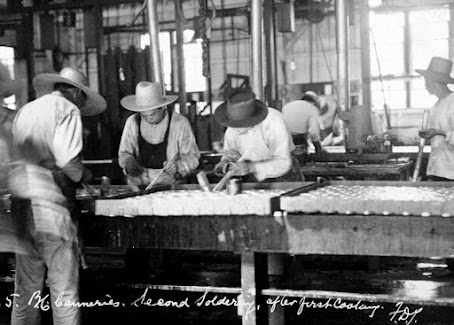

After canning, the cans were weighed and underweight cans were “patched” by women who could tell by feel how much extra salmon was required. Once the cans were full, lids were added. Chinese tinsmiths originally soldered the lids on, but the can soldering machine made their jobs obsolete.

(Then came capping the cans and hand soldering them shut.)

After hand soldering lids on, a slight improvement was achieved through this manually controlled soldering machine (shown above).

Early on, the cans were then placed in pressure cookers like the pressure cooker (shown below). This is where the cans of salmon were then cooked to preserve the fish. After cooking, the cans were labeled and packed for shipment.

THE TECHNOLOGY AT NORTH PACIFIC CANNERY CHANGED

As technology changed, so did the appearance of the Cannery. Mechanization of the canning process made the Chinese tinsmiths’ jobs obsolete, followed by those of the butchers as the Iron Butcher grew in popularity. These machines greatly increased the efficiency of production and saved a good deal of hard labor. This made the Cannery more profitable, but of course resulted in the loss of many jobs.

Our tour guide told us about the Iron Butcher (see above).

The above storyboard told us how the salmon needed to be cleaned after butchering. The troughs from the early days were eventually replaced with long wooden tables, or sliming tables, along which several workers could stand. They were equipped with an overhead system of water pipes and faucets, making it easier to wash a larger quantity of fish (see below).

In time the station developed into a double row of stainless steel or aluminum sliming tanks, at which each worker washed fish beneath a continuous flow of cold running water (see below). Once washed, the salmon were then placed onto a conveyer belt headed for the slicing machine.

The storyboard (see above) told us that the salmon are sliced into can-sized pieces. Similar to butchering, slicing was once done by hand, requiring a whole crew of skilled workers. In the early days, they used a hand-cranked cutting machine. And then a rotary power-operated unit was introduced. It had circular saws called gang knives (see below), which were mounted on an axle and spaced out to cut salmon to the regulated portion. The cut pieces were delivered into a bin on the other side of the knives.

The above storyboard told us about the filling and packing of the cut pieces of salmon into cans. In the early days, workers filled cans by hand, and then loaded them onto a tray that fit twelve full-pound or twenty-four half-pound cans.

In later years, European women also worked at the filling station (see above). The fastest workers could fill 20 cans per minute or 1,800 cans in a ten-hour shift. When filled, the cans were loaded onto trays that fit 12 one-pound or 24 half-pound cans. Trays were placed on the top rack of the filling tables where a supervisor inspected them and punched a ticket to record the number of trays each worker filled during a shift.

The rotary fish filler (see below) was invented in 1912, filling cans automatically at a rate of 75 to 120 per minute using a plunging method. Attached was the automatic salter, which was regulated to inject a prescribed amount of salt into each can as it passed through. Despite the advances in mechanization, the filling machine was not perfected until several years later. Hand filling continued in order to ensure a quality product for the discerning market in the United Kingdom.

(Filling machine at cannery showing empty cans entering and filled cans exiting the filling machine.)

(After 1912, this filling and packing machine could fill 75 - 120 cans per minute.)

The storyboard (see above) told us about the weighing and patching of the filled cans of salmon. Filled cans were weighed to ensure that they were filled consistently. In the early days, each can was weighed by hand on a scale before proceeding to the next station. Underweight cans were sent to the patching tables, where workers would top them up with smaller pieces of salmon. By the 1920s, the weighing machine (see below) became a standard part of the canning line. It worked like the manual method, but was faster.

The machine would detect underweight cans on the mechanized line and eject them to the patching area (see below). Once repaired, the cans were put on a conveyer and returned back to the main line.

Shown above is the women correcting the amount of salmon in cans that have been ejected by the weighing machine. Beginning in 1903, the weighing machine was introduced replacing the hand scales. These machines could detect underfilled filled cans and automatically divert them from the assembly line to the patching station. There, salmon would be removed or added to bring the can to the proper weight.

The storyboard (see above) told us about the capping process. Once the cans of salmon were adequately filled, they were topped with lids. In the early days, lids were applied by hand. Each lid had a hole in the center and a small piece of waste tin was aligned underneath the lid, on top of the salmon. This allowed for the steam to escape during the cooking process while preventing solder and water from seeping into the product.

(Capping the can was done by hand prior to the vacuum closing machine.)

The vacuum closing machine (see below) became a standard part of the canning line by the 1920s, and automatically placed lids onto cans before sealing them shut. Manual labor was drastically reduced, as only one worker was required to ensure the machine ws stocked full of lids.

(By 1920, the vacuum closing machine above was invented as well as the clincher.)

Next the can lids were clinched on. In early years, they were soldered by hand. Later a manually controlled soldering machine was used. After manufactured were in use in the early 1900s. A machine called the clincher was used (see below).

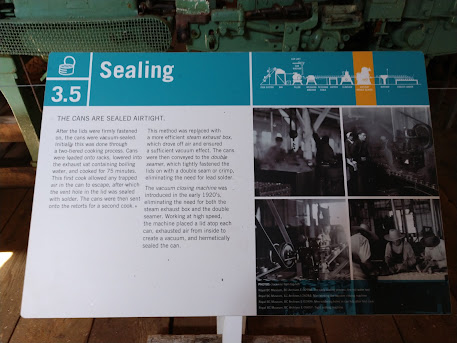

The storyboard (see above) told us about sealing the cans. After the lids were firmly fastened on, the cans were vacuum-sealed. In the early days, this was done through a two-tier cooking process. Cans were lowered onto racks, lowered into the exhaust vat containing boiling water, and cooked for 75 minutes. This first cook allowed any trapped air in the can to escape, after which the vent hole in the lid was sealed with solder. The cans were then sent into the retorts for a second cook.

This method was replaced with a more efficient steam exhaust box which drove off air and ensured a sufficient vacuum effect. The cans were then conveyed to the double steamer, which tightly fastened the lids on with a double seam or crimp, eliminating the need for lead solder.

The vacuum closing machine was introduced in the early 1920s, eliminating the need for both the steam exhaust box and the double seamer. Working at a high speed, the machine placed a lid atop each can, exhausted air from inside to create a vacuum, and hermetically sealed the can.

Introduced in the 1920s, the vacuum closing machine (shown above) sealed the cans inside a vacuum chamber. Manual labor was drastically reduced, as only one worker was required to ensure the machine was stocked full of lids.

The storyboard (see above) told us how the cans were loaded onto trays in preparation for cooking. Sealed cans were loaded onto giant trays called coolers. The coolers, when filled, were stacked on cars and wheeled into the retorts for cooking. In the early days, this process involved several workers loading the trays by hand. Eventually, the Bussey System was introduced, an invention that automated the loading of retort cars and reduced the amount of labor required at this stage in the canning line.

Later on crates of cans would be stacked into these rolling carts and wheeled into larger pressure cookers which could process many more cans at once in a fraction of the time (see below).

The storyboard (see above) told us how the trays of canned salmon were loaded into the steam retort and cooked. The cans were cooked in large retorts or steam ovens. In the early days, the original cooking system was two-tiered-- the first cook was done in a vat of boiling water to allow for any trapped air in the cans to escape. The second cook was done in wood retorts for 65 minutes to ensurea thoroughly cooked product.

Over time, the retorts were changed to cylindrically shaped metal chambers that are still used in modern plants. Racks of canned salmon were wheeled into the retort, the heavy door was closed or lowered, and the steam was turned on to a pressure of 116 degrees Celsius (240 degrees Fahrenheit) for a single cook of about 90 minutes.

Chinese cannery worker loading a tray of one-pound cans into a retort. Retorts, large steam-heated pressure cookers, were used instead of hot water baths. This change increased the consistency of the product. Trolleys of filled cans were cooked for 90 minutes.

The storyboard (see above) told us how the cans were washed. In the early days, after exiting the retorts, cans were washed in a caustic soda bath to remove any grease. They would then be hand-rinsed and sent to a storage area for cooling. In later years, a mechanized washing machine received trays of canned salmon, rinsing off excess grease and debris (see below).

The storyboard below told us how the trays of cooked salmon were cooled. In the early years after cooking, racks of canned salmon were taken to a warehouse to be cooled. The cans needed upwards of 24 hours to be thoroughly cool before they could be labeled, packaged and shipped. In the later years, the steaming hot cans from the retorts were submerged in a cold water bath and then sent on for inspection and packing.

Testing and resealing the cans were specialized jobs, often held by Chinese workers, ca 1913 (see above). This method of testing began to dwindle around the 1920s with the introduction of new technologies such as the sanitary can and the vacuum closing machine.

The storyboard (see below) told us how the cans of salmon are tested to verify a proper seal. After cooling, cans were tested to determine if they were properly sealed. In the early days, workers used wooden mallets to sharply tap the lid of each can. A clear sound indicated a proper seal, while a dull sound revealed an improper seal. Cans that didn't pass were punctured with a sharp instrument on the other side of the mallet, releasing any pressure from inside. The hole then was quickly brushed clean, bonded with solder, and sent back to be cooked once more.

The storyboard (see below) told us how the cans are labeled before being boxed. Cans were often labeled at the cannery before being exported. At first in the early days, this process was done by hand, which was both labor-intensive and costly. The labeling machine revolutionized packaging at the cannery, intricately applying glue and a label to each can at high speed.

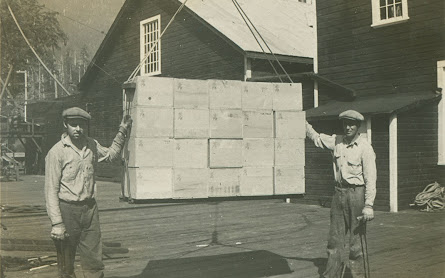

The storyboard (shown below) told us how the labeled cans are boxed. Cans of salmon were place in wooden boxes and packed for export. Cans coming off the labeling machine were packed in boxes manually. Unlabeleds cans were boxed using a box-up machine, which would shunt cans into each box. The lids were applied manually and nailed down with machinery. Eventually cardboard replaced wooden boxes, providing a more econimcal and versatile container for shipping.

Crew at the North Pacific Cannery working the box labeling machine.

(Two cannery workers preparing to load crates of canned salmon into the hold of a steamship for transport.)

The storyboard (shown above) told us about the warehousing and shipping. Once boxed, the canned salmon was stored in a warehouse facility at the cannery until either exported to markets in Europe or North America or shipped to a centralized company warehouse in Vancouver or Victoria.

(Half pound cans stacked to the roof beams in a warehouse, ca 1913.)

In the early years cans were hand packed in wooden crates. Later, cans were packed using a box-up machine, which would place cans into each box. The box lids were applied manually and nailed down. Cardboard subsequently replaced wooden boxes providing a more economical container for shipping. Once boxed, the canned salmon was stored at the cannery or centralized company warehouse. From there the product was distributed throughout North America or exported to markets in Britain and Europe.

After we finished our tour inside the Main Cannery Building, we went outside along the Reduction Plant area.

In 1945, a fish Reduction Plant consisting of two new buildings was built at the far end of the wharf.

In 1955, three buildings were demolished and a larger fish Reduction Plant was built consisting of two tanks for fish oil, a boiler house and the reduction building itself. In 1956 and 1957, two more tanks were added for the bunker oil and water needed to run the plant.

The Reduction Plant was associated with the changes to the Cannery to accommodate new functions in relation to changing technology and markets. These buildings using wood-frame construction, were clad with metal siding and mounted on wooden pilings. They had a conical form including the boiler house smoke stack and the offal pit.

These buildings were built to process salmon offal in the summer and whole herring in the winter. The offal was cooked in pressure cookers, and then a press removed the liquid, which was boiled to generate fish oil. Solids produced by this process were dried, bagged and sold as animal feed.

In 1968, after the herring fishery had been banned for several years, the Reduction Plant ceased operation and was closed. The plant was reopened in 1972, when it was reactivated for the processing of fish oil and meal for animal feed and fertilizer. The plant was shut down permanently in 1980.

Therefore, four large metal tanks were associated with the Reduction Plant. Two of the tanks were used in fish oil storage, and the other two contained water and fuel oil for the plant. They were supported on pilings, which imparted a distinctive appearance to the reduction complex.

At the Reduction Plant, fish offal was pressure cooked to separate fish oil from solids. The fish oil was used in products such as paint and cosmetics, and the solids wsere sold for fertilizers and animal feed. While two of the holding tanks stored the reduced fish oil and the other two held the water necessary for the reduction process.

Another small building on the southeast corner of the Main Cannery Building was constructed following completion of the access road in 1959 to enable delivery of fish offal for processing in the reduction plant. The fish reduction function kept the North Pacific Cannery in operation when decisions were made to close other canneries in the region.

There was a wanted poster (see below) proclaiming that if we found the picture of John Carthew, the founder of North Pacific Cannery, we could claim a prize at the gift shop. I found him lurking behind a big window on the second floor of the Main Cannery Building (see above). My prize was a pencil!

Next, we saw the Manager's House (ca 1916). It was a one and one half story gable-roofed frame building, faced with drop siding, with return eaves adding interest to the roof structure. The manager was said to be cruical to the success of each season, and one of the perks of this high-pressure position was having the largest single-family residence on the site.

The Manager's House (see house below on the left) was constructed with wood from the Georgetown Mills, and built identical to the adjacent Assistant Manager's House until modified in 1924 with the addition of a side addition and a dormer window. (The modifications to this large house siting on the embankment side of the boardwalk, with an accompanying yard and garden emphasized his status as the manager, while its positioning near the Cannery buildings reflected his role in managing the overall site.)

The Assistant Manager's House (ca 1918 -- see house to the right above) was located right next to the manager's house. This was built two years later in the same style as the Manager's House for the assistant manager and his family. Positioned on the embankment side of the boardwalk, it possessed a small yard.

Next, we walked to the Company Office (shown above on the right). The functional design of the Company Office -- with its gable-roof and one and one half stories -- was erected in 1956 when the Cannery was converted to a year-round operation. It is situated in front of the former manager’s residence to the east of the reduction plant. The office served as the nerve center for the site. Here, records on the Cannery’s operation were kept, people were hired, and contracts with fishing bosses were signed. Currently, it houses the offices of the North Pacific Cannery Village Museum.

We got to take a look inside the Company Office that was full of office machines and equipment.

The Company Office also had ledgers (see above) and payroll records (see below).

It is interesting to note that the Japanese workers at the North Pacific cannery performed many different jobs. The inherent structure of the segregation and racial ideas of the time were apparent in the way payment was given. In the payroll records from the North Pacific Cannery, we can see the record of employees, the jobs they performed and the payment (hourly or monthly) they received. The Japanese workers worked for hourly wages instead of a monthly salary, with some Japanese laborers working ten or twelve hours a day and other days only a few. There is also some evidence, which suggests that, these fishermen arrived before the fishing season to work at these odd jobs and then transferred to fishing once the salmon were running.

Wages for Japanese shore workers were often listed under house name. The majority of the workers were given the title of general labor, although some jobs such as nets, and carpenters helpers and carpenters were specified. The wages were paid for hourly work, and unlike many European workers room and board was not included.

Our next stop was the Company Store (ca 1939). The functional design of the wood-frame company store with its one and one half story gable roof and shed-roof extensions illustrates its dual role as a place for workers to get provisions as well as a community center for get togethers. It was believed to have been brought to its present site by barge from another Cannery. The building illustrates the self-sufficient operations which were a goal of the Cannery owners. The Company Store was the source of provisions, clothing, tableware, hardware, and other goods for Cannery workers. Workers could receive advances on their wages in the form of coupons, which they used to purchase goods sold by the company.

We walked inside the Company Store for a look -- the shelves were stocked full just like when the North Pacific cannery was in production (see pictures above and below).

Besides food, there were dishes as well as pots and pans in the Company Store.

There were also things like a sewing machine, clothes, a wash basin, a wood burning stove, and irons in the Company Store (see above). And below is a meat cutter, scale and wrapping area for freshly caught salmon -- if workers chose to purchase some for their family.

The Company Store also had an area to play cards (shown above) -- part of the community center appeal, while below our tour guide shows how they played records in the Company Store.

Although the cannery was fairly large, most of the buildings were very close together. Housing, the Company Store and the Company Office along the shore side of a long boardwalk (right in the below picture), and the “workers” buildings were located on the water side (see left side of below picture).

The cannery workforce was multicultural but segregated, and due to the isolation, housing had to be provided during the canning season for all but some of the First Nation workers. Japanese workers fished and mended nets. Chinese worked on the cannery line. First Nation workers fished and worked on the cannery line. Europeans were management and did some fishing. The North Pacific Cannery still has most of the European housing buildings and some Japanese housing intact, although the Chinese and First Nation housing is gone (see below picture).

The European Housing (ca 1940 - 1950) shown above, accomodated high-status European employees with families, such as the lineman and the storekeeper. The houses designed for Euro-Canadian workers and their families, included shallow-pitched, gable roofs, porches, drop siding and plywood skirting. Of identical form and plan, they illustrate the utilitarian approach to the provision of standardized workers’ housing at resource communities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

A row of housing at the North Pacific Cannery looking toward the canning facilities.

Next to the European Housing for the workers on the shore side -- just a little more down the boardwalk -- was the Watchman’s House (ca 1940). This one and a half story cabin with a gable-roof was faced with bevelled siding, and situated on the embankment side of the boardwalk extending to the east of the main Cannery complex.

Almost directly across from the Watchman’s House is the Net Boss’ House (ca. 1960). This small one story building is square and gable roofed, and clad with drop siding. Resting on pilings over the water, it formerly housed the net boss of the Cannery. Though he did not have quite the same status as management, the fishermen regarded him as the most important man on the site. The building currently functions as a space for the local ham radio club.

(Buildings in picture shown above -- starting at the middle of the picture is the white Railman's House, then the European Bunkhouse, then the Mess House located across from the European Bunkhouse, then the Shikitani House, and finally the Japanese Bunkhouse at the end. Not seen in the picture, but located across from the Shikitani House were the Triplex Units.)

Next, we saw the Railman's House (ca 1916), just down from the Watchman's House. This building was once a siding office for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, following the building of the rail line that skirted the Inverness Passage. Its original location was adjacent on the north side of the tracks, immediately adjacent to the North Pacific Cannery site. Following its acquisition by the Cannery, the building was moved a short distance to its present site on the embankment side of the boardwalk to house workers with families.

Following the Railman's House was the European Bunkhouse (ca 1952). It is a two-story structure (see above) that was added to meet the expanded accommodation needs of the workforce at this late stage in the Cannery’s operation. It served as living quarters for single European men who worked in teh company office. Of rectangular form, the gable-roofed building is clad with plywood panels similar to the facing materials of the Cannery and Packing buildings. It is located on the embankment side of the boardwalk immediately to the east of the railman's house. Today it function as a Bunkhouse Hostel providing gueat accomodations.

The Mess House/Restaurant (ca. 1949) is a one-story building located on the boardwalk across from the European Bunkhouse (see picture of inside of Mess House above). For the last 50 years of the Cannery’s operation, it was the Mess House/Restaurant for European workers at the site.

Prior to the building of the European Bunkhouse, the Mess House was located on the embankment side directly across from its current site. It's a cheery informal space with tables bearing red and white tablecloths, standing on bare wooden boards. Currently, it continues to serve as a restaurant for museum staff and visitors. The highlight of the menu is the salmon chowder -- a tribute to the fish which were once landed here by the ton.

The Triplex Units (ca 1964 - 1965) are gable-roofed buildings, clad in plywood panels (see above and below). These buildings provided self-contained accommodation for Cannery workers during its last years of operation. Faced with plywood lapped to resemble siding, they are located on the embankment side of the boardwalk to the east of the two-story bunkhouse.

In the pictures above and below are the Shikitani House (first white house on the right) and then the Japanese Bunkhouse (right behind the Shikitani House on the right).

Housing for Japanese workers included the Shikitani House (ca 1938, shown above), a one-story dwelling sheathed in vertical board-and-batten paneling. It was constructed in the 1930s to house Tak Shikitani and his family. Tak Shikitani was a spokesman for the Japanese workers at the site. In the 1940s, the buildings were used to house summer student workers at the Cannery. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Shikitani family again lived in the building during the summer.

Inside of the Shikitani House is shown above and below. The kitchen area is in the above picture, while the living area and bedroom pictures are below.

(Japanese children playing on the wharf.)

The Japanese Bunkhouse (ca 1930, shown above), a one and one half-story structure has a shed-roof extension, tapered siding, multi-pane windows, an original layout -- including the the division of space into small compartments for individual fishermen, and a separate washhouse wing at the rear. Before the Second World War, the Japanese Bunkhouse housed seasonally-employed Japanese fishermen, boat builders, and carpenters at the Cannery. During the late 1950s and 1960s the bunkhouse was managed by the Miki family. The multi-pane glazing of its windows is an exterior feature of interest.

Besides being segregated in how they were paid for working, the Japanese workers were also segregated when it came to housing. This was not unique to just the Japanese workers -- as housing on site at the cannery was divided for people of all ethnicities. Since the workers at the canneries largely consisted of men, this lead to bunkhouse style housing for the Japanese workers, although there were some houses built for families.

From the period of 1918 until 1923 the Japanese workers were divided into houses, these houses varied in name over this time period, and varied from three to four distinct houses. Tanaka House, Matsumoto House, Tanino House, Kurita House and Hayashi House were the different names of these houses, although not all existed at the same time. These house names often came from the family who started each house. Some of the Japanese houses still remain at the North Pacific Cannery -- the Shikatani House and the Miki House -- and show a part of the life that was present at the cannery. Once families of Japanese fishermen began arriving, individual residences were built. The wives of the fishermen and shore workers often worked in the cannery cleaning salmon in slimming tanks.

(Women cleaning fish at the cannery.)

The Japanese Bunkhouse had many different rooms including the "sit bath" at the rear of the house (shown below). Known as the traditional ofuro, it is a Japanese wooden bathtub often with deep, straight sides. Simple and beautiful, ofuro tubs were intended more for relaxation and warmth than for actual bathing and washing.

There were rooms for a small cot or desk (see above and below).

Above Mel walks through the Japanese Bunkhouse.

(Dinner table at the Japanese Bunkhouse.)

Below is a sitting room in the Japanese Bunkhouse.

The kitchen area and cupboards in the Japanese Bunkhouse.

A piano (shown above) and another bedroom (shown below) in the Japanese Bunkhouse.

Across from the Shikitani House would have been where the Japanese Net Loft was. This building served as a space for net storage and mending for the Japanese fishermen. Long after the cannery operations ceased, the building collapsed and was washed away with the tide.

Above is the site where the Japanese Net Loft would have been.

The Boat Life Shed had two winches. On the decking to the south of the Main Cannery Building is a small shed that formerly sheltered the motor powering the boat lift. Two winches associated with the lift are still housed inside this structure.

Seagulls are on the dock railing at North Pacific Cannery (see below).

Next, we went into the Salt Shed (ca 1900, shown below), which was connected to the Main Cannery Building. The Salt Shed originally provided extra storage for tinned salmon, and later salt. Today it houses an interactive model train display and an exhibit about Port Essington.

The model train was pretty neat. When we put a loonie in the coin box, the miniature railroad trains chugged around the tracks (see below).

The Grand Trunk Pacific Model Railroad Society was formed by a group of rail enthusiasts in 1980. In 1986, they moved into the North Pacific Cannery Village Museum. The Club currently occupies two large rooms in what used to be the Salt Shed. One of these rooms contains a large Lionel 'O' gauge layout, consisting of about 1,000 feet of track, 50 switches, and 27 vintage Lionel locomotives plus rolling stock. Also included in this display is a 'HO' layout with about 400 feet of track. These two layouts have no scenery, but are very spectacular to look at. This display was inherited by the Cannery Museum from the collection of the late Norman Kinslor of Prince Rupert, B.C. It is operated and maintained by the Model Railroad Society.

The second large room contains a 'HO' layout. This layout is a model of the Skeena River, circa 1950, with a scale model of the cannery complete with C.N. trains running past the cannery as they still do to this day. This display is free -- we just had to push a button and the train runs. This diorama was constructed completely by Club members.

Also in the Salt Shed were some historical photos (see below).

The picture above shows the Columbia River skiffs at the North Pacific Cannery with fishing boats coming into the cannery.

Above is a typical well-equipped wheelhouse from the late 1940s or 1950s.

And that was the end of our fabulous tour of the North Pacific Cannery. It was well worth the money!

We then drove into Prince Rupert to go walk the Rushbrook Trail, a 1.8-mile out-and-back trail near Prince Rupert.

Below, Mel poses by the trailhead sign. This trail is located on the traditional territory of the Tsimshian and follows the coast.

A piece of history about the Rushbrook Trail is that it was originally constructed by the City of Prince Rupert in 1985, but it closed in 2003 due to safety issues caused by rock and debris slides. This prompted the city to begin fundraising in an effort to reopen the trail to the public. The Rushbrook Trail restoration was originally developed as a community lead project through the Port Authority, with the intent to re-connect the local community to the expansive ecosystems and differing environments of the Island. In 2018, after having been closed for 15 years, the Rushbrook trail reopened to the public. The $1.1 million rehabilitation project resulted in the pristine waterfront walkway the community knows and loves today.

The trail provides excellent access through otherwise formidable coastal terrain allowing access to both lush rainforest experiences as well as to the beauty of sub-alpine meadows. The first 3/4 of a mile on the trail gently climbs through the lush undergrowth of a coastal rainforest and yes....some tall trees.

Along the way, there are three pre-fabricated aluminum span bridges over the Prince Rupert Harbor (see the first one above).

Mel pauses to look at the view along the trail.

We spot the wreck of an old freighter (see above).

Continuing on, the trail winds steeply upward.

And even thogh there are some relatively steep hills to climb in some areas along the trail, it's simply beautiful!

Every so often there were benches looking out to the water (see above).

Above is a closer view of the wrecked freighter.

Above is what looks like old railroad wheels.

The end of the trail was rather anticlimactic when it opened up to a scruffy boat yard with no directions of where to go next. We turned around and retraced our steps back to the beginning of the trail.

Below is the trail marker at the other end of the trail.

As we walked back the trail, I took another picture of the wrecked freighter.

We walked by an area on the trail where water was dripping through the moss and vegetation, over the rocks like a little waterfall (see above).

And we're back on the trail and over the three bridges we go once again.

We're approaching the beautiful Prince Rupert harbor.

And then we are back at Bob's on the Rocks where the trail started.

We then walked out to the Prince Rupert harbor to enjoy the spectacular views.

There were lots of boats in the Prince Rupert harbor.

We drove away from the harbor and followed the road to the Prince Rupert Cruise Ship Terminal where we saw a Carnival Miracle Cruise ship in port.

The Kazu Maru, a 27–foot Japanese fishing vessel, is on display on the waterfront at Prince Rupert.

The vessel itself is nothing special to the untrained eye, but it’s story is captivating -- spanning the Pacific Ocean on an unintentional journey from Owase Japan to the northwest coast of Canada. The story of the Kazu Maru follows below:

In September 1985, Kazukio Sakamoto took his vessel, the Kazu Maru, out to fish in local waters. Tragically neither he nor the boat returned home. A year and a half later, the Kazu Maru was found in Skidegate Channel (the body of water that separates the north and south islands that make up Haida Gwaii) by the DFO patrol vessel Sooke Post. It was quickly established that the overturned vessel had been at sea a considerable time.

Eventually the Kazu Maru was taken to Prince Rupert where she was restored and an open shed was built for display. A plaque nearby commemorates her voyage and a park surrounds the shed, built as a dedication to all mariners whose lives have been lost at sea. Sakamoto’s wife referred to the Kazu Maru as ‘the love of his life’ and indicated he would have been happy to know the little craft was part of a park honoring mariners, while recognizing the danger of a life at sea. Coincidentally, the two cities of Owase and Prince Rupert had become ‘sister cities’ in 1968 so it’s appropriate that this stoic little craft should find its way across the seas to her ‘second home port’ of Prince Rupert.

In the Rotary Waterfront Park in Prince Rupert is the Kwinitsa Railway Station Museum (see below).

Mother Grey Whale and Calf statue (see below) is in the Rotary Waterfront Park in Prince Rupert. The whale statue was carved by Hans Siniarrski and donated to the City of Prince Rupert in 1985 in celebration of the 75th anniversary of the community. Unfortunately, Hans passed away before the statue was completed and the whale was not resurrected until 1998.

Another look at the Carnival Miracle Cruise ship in port.

The Wheelhouse Brewing Company that was established in 2013 in Prince Rupert.

Above is the Pillsbury House, which has the historical distinction of being Prince Rupert's first home - circa 1908. It was built for and was occupied by Grand Trunk Pacific railroad dignitaries and their families for a century. If this home could talk, it would disclose the conversations, dreams, and plans of Joel H. Pillsbury, 1st Assistant Harbor Engineer (the original builder) and Charles M. Hayes (founder of the Grand Trunk Pacific). No doubt they spent many hours sitting and troubleshooting their aspirations and hopes for the city of their dreams. Joel Pillsbury was a city planner and designed the house with the four upstairs gables facing the four points of the compass.

Then after getting gas at the 7-Eleven in Prince Rupert, we drove back to the campground and had a dinner of chicken drummies and potato wedges.

We then drifted to sleep dreaming about the fantastic tour we had at the North Pacific Cannery today and the calming sound of coastal waters!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment