We got up this morning and got rolling by 8:20 a.m. It was smoky, but sunny out with a starting temperature of 52 degrees.

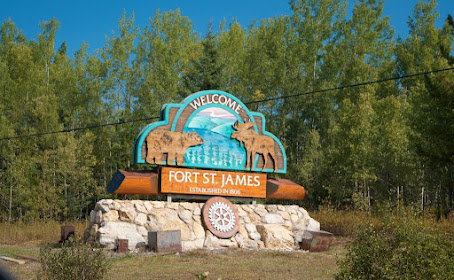

We again are traveling on the Yellowhead Highway with a plan to stop in Fort St. James, BC tonight.

We have 77 kilometers or 48 miles to Burns Lake. Within about 15 miles, we have come to Topley. Topley is a village in northern British Columbia with a population of 330, and is located on the Yellowhead Highway between Houston and Burns Lake. It is named for the photographer William James Topley.

The sky is beautiful with white fluffy streaks splattered across the sky.

We now have 221 kilometers or 137 miles to Fort St. James via Highway 27.

Up ahead we see construction, just before we get to Burns Lake.

We have now arrived at Burns Lake. Burns Lake has a population of 2,726 and an elevation of 2,300. It is located on Yellowhead Highway 16, just 140 miles west of Prince George. Burns Lake had its modest beginnings in 1911, as the site of railway construction. Today, forestry is the mainstay of the economy, along with ranching and tourism.

It is now 67 kilometers or 42 miles to Fraser Lake, while it is 222 kilometers or 138 miles to Prince George. And again, another section of road construction.

We are now at Fraser Lake, an attractive lakeside community with a population of 1,354 and an elevation of 2,200 feet. The pioneer roots of the area’s history date back to the fur trade, with the establishment in 1806 of a fur-trading post by Simon Fraser, at Fort Fraser near the east end of Fraser Lake. The modern day town was established in 1914, during the construction of the Grand Trunk Railway, and was incorporated as a village in 1966.

The east end of Fraser Lake is recorded as the site of the first cultivated land in British Columbia, while Fort Fraser is the site of the last spike of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, now the Winnipeg-Prince Rupert line of Canadian National. Fraser Lake marks the eastern edge of the Lakes District, and is located in a land dotted with lakes, rivers, mountain ranges and valleys, where outdoor recreation truly knows no limits. Today, tourism, mining, cattle ranching and the saw mill are the mainstays of the local economy.

Prince George is now 155 kilometers away (or 96 miles). And as luck would have it, another patch of road construction awaits us.

Fort Fraser, with a population of 950, is one of the oldest settlements in British Columbia and named after the explorer Simon Fraser, who established a trading post here in 1806. It is now a supply center for surrounding farms and sawmills. The last spike of the Grand Trunk Railway was driven here on April 7, 1914.

Vanderhoof is now 37 kilometers or 23 miles away, Fort St. James is 84 kilometers or 52 miles away, while Prince George is now 134 kilometers or 83 miles away.

Vanderhoof has a population of 5,000 and an elevation of 2,225 feet. It is located 60 miles west of Prince George on Yellowhead Highway 16. Vanderhoof is the geographical center of British Columbia on the Alaska Circle Route, and on your way to and from the northwest coast of B.C. The town was named for Chicago publisher Herbert Vanderhoof, who was associated with the Grand Trunk Railway. Today, Vanderhoof is the supply and distribution center for area agriculture, forestry and mining and is a great stop for shopping, history, and beautiful scenery.

We passed the turnoff for the Fort St. James Historic Park, and then went past the sign for the turnoff to the Fort St. James National Historic Site.

We now entered a wildlife corridor.

Fort St. James is now 27 kilometers away (or 17 miles).

Fort St. James is a former fur trading post in north-central British Columbia. It is also the gateway to a chain of rivers and lakes that traverse 400 kilometres of central British Columbia. The population of the Fort St. James area, including the municipality itself, rural areas and First Nations, is approximately 4,500 people.

Stuart Lake in Fort St. James is one of the largest natural fresh water lakes located in British Columbia providing over 171 miles of shoreline to explore. The northern village of Fort St. James and many of the local community parks in the region rest on the southeast shores of the 56 mile long lake. The largest width of Stuart Lake extends 4 to 6 miles from shore to shore. The community of Fort St. James is the easiest point to access the lake via a paved road.

The Cottonwood Municipal Campground is located at 821 Lakeshore Drive on the waterfront of Stuart Lake. This is where we stayed for one night for $25 CA (or $18.22 US).

After getting all set up, we had lunch and then left at 12:30 p.m. to head to the Fort St. James National Historic Site. Our Parks Canada annual pass that we had bought when we first were in Canada got us in free (would have cost us $7 CA/each or $5.10 US/each).

The Hudson's Bay Company at Fort St. James was incorporated by the English Royal Charter in 1670. The company was granted a commercial monopoly over the entire Hudson Bay drainage basin, known as Rupert's Land.

(Shown above is the Fort St. James Site Plan from Parks Canada Brochure.)

Fort St. James National Historic Site of Canada is a heritage village on the east shores of Stuart Lake, British Columbia. It recreates the lifestyle and conditions experienced by the First Nation people, fur traders and the early pioneers in the late 1800s.

The Fort St. James National Historic Site was founded by the North West Company explorer and fur trader Simon Fraser in 1806. It came under the management of the Hudson's Bay Company in 1821 with the forced merger of the two battling fur companies.

Also known historically as Stuart Lake Post, it is one of British Columbia's oldest permanent European settlements and was the administrative center for the Hudson's Bay Company's New Caledonia fur district. The fort, rebuilt four times, continued as an important trading post well into the twentieth century. Now the fort is a National Historic Site of Canada, with some buildings dating to the 1880s. Each heritage village building has a story to tell and is connected by a raised boardwalk path.

The present appearance of the fort itself is largely to the credit of one person — Roderick MacFarlane. Charging bull-like into the district in 1888, he set about the much-needed construction of a “new post” during a time of economic restraint, and without approval from his superiors. With A.C. Murray as his foreman, MacFarlane started on the fish cache, fur warehouse and interpreter’s house only months after his arrival. This involved dismantling and reusing much of the building materials from the previous post. We have MacFarlane’s determination and outright disobedience to thank for Fort St James continued existence, its present layout, its buildings and boardwalks, as well as its approximate mile long of fencing, made up of six types, each suited for its particular purpose.

After watching a couple of films in the Visitor Center museum area including the short film, “A Letter Home”, which summarizes the fort’s past, and “If Walls Could Speak," original footage from 1977 of the restoring of Fort St. James, we went outside to begin our self-guided walking tour.

The above picture shows several of the Fort St. James National Historic Site buildings starting with the Warehouse & Fur Storage building (1888-1889) in the center, the Trade Store (1975-1976) on the right in the front, and the Officer's House in the background on the right. Also of note is the flagpole with the Hudson's Bay Company flag flying in the breeze.

(Closeup of Hudson Bay Company flag.)

The Flag Raising tradition has occuried for a long time. In 1670, when the Charter of the Hudson’s Bay Company was granted, the Company was allowed to fly the “King’s Jack,” or the combination of St. Andrews and St. Georges Crosses. Until this time, only the Royal Navy could fly the King’s own flag. But the charter granted the Company of Adventurers not only sole trading rights over the vast territory of Rupert’s Land, but also gave it the power of governance on the King’s behalf, and was authorized, “if necessary to send either ships of war men or ammunicion unto any of their plantations, forts, factories or places of trade aforesaid for the security and defense of the same…or otherwise to continue or make peace or war…” In essence, the Hudson’s Bay Company was the King’s representative and army in Canada. From Hudson Bay Company ships the Union Flag was apparently transferred to the Company’s posts such as at Fort St. James.

Adopted around 1818 as a symbol of the Company, its forts, ships and personnel, the ensign is made up of the British Union Jack on a red field with the letters “HBC" for Hudson’s Bay Company. When the Northwest Company amalgamated with its rival the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821, the company operated under the Hudson’s Bay name. And that’s the flag that has flown here daily since 1822. If you look, you can see the letters HBC in white against the red background.

* * * * *

The Fort St James National Historic Site, originally established by Simon Fraser for the North West Company in 1806, displays one of the largest groups of original wooden buildings representing the fur trade in Canada. The story revolves around the relationships and interactions between the fur traders and Native Peoples of the region, namely the Carrier First Nations.

Who were the Carrier People?

The Carrier were members of the Athapaskan language group and lived in the north central interior of British Columbia on lake and river tributaries of the Upper Skeena and Fraser rivers. Carrier people called themselves “Dakelh-ne” or “Yinka Dene,” or they identified themselves by the community from which they came with the addition of the suffix “t’en” or “whut’en” (people of). There were three dialects of Carrier people: 1) “central” spoken by the Carrier people around Stuart and Trembleur Lakes; 2) “Babine” spoken by the Carrier people around the Bulkley River and Babine Lake; and 3) “southern” spoken by the Carrier people around Quesnel and in the Anaheim Lake areas.

Many of the Carrier families became trade partners with the newcomers who set up posts in their region in the early 1800s. Some of the more prominent Carrier traders of the 19th and early 20th century fur trade were Qua, Simeon Le Prince, Gross Tete, Tayah, and Joseph Prince. The alliances between Carrier and fur trader were forged through trade ceremonies, gift giving and sometimes marriages between Native women and the fur traders. While the Carrier expectations of this relationship leaned toward mutual loyalty and reciprocal obligation, the fur traders hoped the connections would ultimately translate into smoothly-operating system of profits for the Company’s business.

However, the traditional economy of the Carrier was based on fishing, rather than on fur trapping. And so it was with much frustration — and limited success — that the fur trade companies encouraged the Carrier to adopt the necessary changes in their seasonal round, tools, and activities to get a sometimes-profitable trade in furs established. One obstacle was that, like the salmon fisheries, access to beaver and the beaver lands was proprietary and based on a ceremonial network of potlatching, clans, and inherited titles. The fur traders likely found this social reality both annoying and incomprehensible, and they spent considerable effort to overcome these “obstacles” to rallying a “useful” fur trapping workforce.

Even though this area was “home” to the Carrier people, to the fur traders it was “wilderness,” and the assignment to one of the cluster of posts in the northern fur district known as New Caledonia was a dreaded posting. Company officers and laborers alike lamented their “exile” to this “Siberia of the fur trade.” Their methods and strategies were first for survival, then for Company profits and they were hard learned and depended upon the relationship they could negotiate with their Carrier neighbors.

Hardships, adventures, challenges and changes were all part of the story of this place. In 1805 and 1806, the North West Company constructed the first two permanent fur trade posts west of the Rocky Mountains. The second, Fort St. James, became the center of the northern fur trade district, known as New Caledonia. In July 1821, the North West Company amalgamated with the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Fort St. James operation continued on the original site until 1952.

Today Fort St. James has been restored to a single year in time -- 1896 -- and the story we discovered here spanned over 146 years, starting with the arrival of the fur traders and ending in 1952, when the Hudson’s Bay Company closed shop on the original site. The years of early contacts and the decades of trade between the Carrier and the Euro-Canadian newcomers were an era of important changes and adjustments.

* * * * *

Above and below are some of the crafts from the Carrier First Nations people. They were indigenous people from the central interior of British Columbia. Most Carrier people called themselves Dakelh, which meant “people who go around by boat."

Above is a historical marker to David Douglas (1799-1834), who was a pioneer botanist of western North America. His name was been given to the mighty Douglas Fir. He had visited Fort St. James in 1833.

Above is a Fort St. James historical marker that is located just to the right of the main entrance at Fort St. James National Historic Site. The inscription says: “Simon Fraser and John Stuart established Fort St. James among the Carrier Indians in 1806. Originally a North West Company post, it passed to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821. From the beginning an important center of trade and cooperation with the Indians, it became, under the Hudson’s Bay Company, the chief trading post in north-central British Columbia and the administrative center of the large and prosperous district of New Caledonia. Throughout its history, Fort St. James has been an important link in communications with northern British Columbia."

In the picture above is where we began our tour -- by going down the boardwalk to walk along the grassy banks of Stuart Lake.

The Wharf and Tramway (1894-1914) was the culmination of many years spent refining trade and transportation routes on the Pacific slope. This area recalled the relatively short period of time when schooners and steamers plied the waters of the Stuart and Babine Lakes and the mighty Skeena, Fraser, and Nechako Rivers. In the 1890s, the tramway was the fur traders’ connection to the rest of Canada and the world. By then pack trains of horses and mules, and teamsters with draft horses, oxen and wagons had replaced the dog teams, canoes and boats of earlier days. All would eventually fade in 1914, when the railroad, and then cars and highways, forever changed the way goods moved and men and women worked in the northern interior of British Columbia.

Shown above, look how steep the tramway is. It took 6 to 8 men with ropes over their shoulders to pull the loaded carts up to the warehouse. And just imagine what it took coming down to prevent a cart full of furs from ending up in the lake.

* * * * *

The first stop on on our self-guided tour was the heritage building, the General Warehouse & Fur Storage (1888-1889). It is one of the finest example of Red River framing (or “piece-on-piece construction”) in North America. This style of construction was originally used at fur trade posts in the Red River Valley of Manitoba, thus the name. This style of construction was perfectly suited to accommodate the changing needs of the fur trade. Because of “bottom log rot,” a post’s buildings had to be renewed about every twenty-five years.

Over time, the wood in the General Warehouse & Fur Storage has revealed marks left behind by the men who built it. The oils in their hands left distinct prints that can be seen on the ceiling of the warehouse to this day. The walls are also covered in tally marks and the signatures of people who worked at the fort. As the workers counted hides, they would mark the walls to keep track.

Officer A.C Murray recounted his work at the fort counting the furs: “We repriced every skin here. Packs were opened and repacked and recounted. I went over the lot myself, over all it, I have counted thousands of skins in my time, perhaps more than any other officer in the company. These furs and our own were then sent to Victoria and repacked for London. They went in the company ships around the horn.”

Today’s General Warehouse & Fur Storage was from the fourth rebuilding of Fort St James. The walls of this unique type of building are comprised of sections or “bays.” When the fur traders wanted to rebuild, they could easily change the size and shape of the new buildings by reconfiguring and reusing bays from previous structures.

The General Warehouse & Fur Storage was piled high with furs, reproductions of trade goods, and original artifacts to give us a sense of the role that Fort St. James played as the distribution/storage facility and administrative center of New Caledonia. Here the goods would wait in preparation for transport to Victoria.

As we looked inside the building, there was so much to see. We saw stacks of supplies, boxes of goods piled high, furs hanging from racks, and bear skins piled up on the floor.

Above Mel is walking through the area with the furs hanging.

Above and below, Mel is checking out the skinned bear in the warehouse. And he is not-at-all “bearly" scared.

(Above is a historical photo of a pack train in front of the Fur Warehouse.)

Outside on the lawn in front of the General Warehouse & Fur Storage is an old canoe.

(Above is a historical photo of this canoe on Stuart Lake.)

Long before the first Europeans (or white men) arrived in canoes like the one shown above, there were native Carrier people. All the land and waters belonged to the Carrier people. They trapped waterfowl, rabbits, and beaver. But it was the waters that gave them life. Every July and August, thousands of salmon swam up the river to spawn in their territory. They built weirs between the islands to direct the salmon into their traps.

When the native Carrier people saw the canoes around the point, they heard singing -- the white people inside the canoes were singing. The singing was in a strange language, something they hadn’t heard before. So they all crowded on the shore to see -- they were very curious of course -- as they hadn’t seen any white men before. The native Carrier people were there when the white men landed (Simon Fraser and those who came with him), and they all started to talk in sign language because they couldn’t understand one another. They showed them different things that they had like a knife and a gun. They fired the gun, and when they fired the gun, the native Carrier people all took to the bushes as they were scared. The native Carrier people had done all their hunting by their homemade tools like spears, snares, and wooden traps.

* * * * *

From the General Warehouse & Fur Storage, the boardwalk lead to the Fish Cache.

By the 1890s, Fort St. James reflected a combination of the Carrier and European influences. Architecturally, no other building illustrated this better than the Fish Cache (1889). The Fish Cache was a wooden structure built on stilts used to store fish and bacon. The Carrier used raised buildings for their caches, often including living trees for the upright posts.

The Europeans fur traders got the idea for their Fish Cache by copying from the local native Carrier people, who had built elevated fish caches to store dried salmon for the winter. The building was raised by four corner elevated posts to deter predators and was built in the “piece-on-piece,” or Red River Frame style -- which was a post and beam construction incorporating hewn “filler” logs.

Today the hewn logs in the Fish Cache bear marks of a long and varied past, having spent many years as parts of other buildings in previous constructions of the post, before finally being incorporated into the Fish Cache you see today. The raised Fish Cache is a recreation of the 1889 structure that once stood on the site. It is raised because it was necessary at the time to protect the food from the various wildlife in the area like bears, coyotes and cougars.

In the early 1800s when Simon Fraser founded Fort St. James, buffalo was the main staple in the diet of many people living on the west side of the Rocky Mountains. Salmon were the “buffalo” east of the Rockies. In 1815 John Stuart, officer in charge of Fort St James wrote, “We have no buffalo or deer, except the reindeer and not many even of those; so that, properly speaking, we may say that water alone supplies the people of New Caledonia with food.”

For decades after their arrival, the fur traders found themselves without the technology or know-how to stay alive in this new land. The traders had to rely on the Carrier who had the tools and skills to trap salmon in weirs, then process and sell the dried fish. Buying local salmon cut deeply into the profits of the fur trade. For decades the traders did not achieve their goal of self-sufficiency, until they finally succeeded in establishing reliable trails, waterway routes and a transportation labor system to bring flour, meat and other provisions to the region.

(In the above historical photo, men stand on the fish cache stairs.)

The native Carrier people's fishing technology was highly specialized and sophisticated. Fish were appropriated by using seven different types of weirs and traps depending on water conditions. The men at Fort St. James in 1820 to 1821 had a daily allowance of four fish per man, while doing work in the winter a man and a dog together got eight per day.

Thomas Dears, a clerk posted to Fraser Lake in 1831, wrote to his friend describing the diet in New Caledonia: “You know I am generally a slender person what would you say if you saw my emaciated body now. I am every morning when dressing in danger of slipping through my breeches and falling into my boots, many a night I go to bed hungry and craving for something better than this horrid dried salmon we are obliged to live upon. These hardships are enough to drive me out of the country.”

In the 1896 era at the fort, George Holder said: “In the early days, getting enough to eat was a real problem. There was no big game, the soil was poor, the growing season short, and we were too far from civilization to import much food. Not only were we dependent on the Carriers to trap the furs, but to catch and preserve the thirty or forty thousand fish we ate each year.”

* * * * *

Our next stop was at the Men's House (1884). Two men from Fort St. James, Long Joe and Vital le Fort, were sent across the frozen Stuart Lake to commence squaring timber for a house that was to be 32 feet by 22 feet. Inside the house was to be a small living area, kitchen and sleeping quarters heated by a brick fireplace.

The pictures above and below show the inside of the Men's House. The newspapers on the wall were used to keep out drafts – they’re reprints of historic newspapers.

The building served first as a clerk’s house. Then it served as a Men’s House, and later as a guest house, a school, and finally, in the mid-1900s -- as a private residence that was used as a base camp for the company employees, boat crews and pack train hands. The pack train hands, who transported goods between posts, used it as their bunk house between trips or while they were waiting for the arrival of the schooner. The “expressmen,” who carried the mail to Fort St. James, also rested in the Men’s House before making their return journeys.

In the 1896 era, if we had walked out onto the fort grounds, we might have encountered men like George Holder, Vitalle LaForte, Louis Grostete, and Donald Todd. These men performed many different tasks at the fort such as cutting firewood, threshing hay, and manning the schooner. Pack trains were integral to the function of the fort and their operators were often colorful characters who would bunk down in the Men’s House.

Cataline was one of British Columbia’s most famous pack train operators. Jean Jacques Caux -- known as Cataline -- was born in rural southern France around 1830. When he first came to what was later known as British Columbia, he packed on a small scale with only one animal. He eventually worked his way up to having larger pack trains with up to 60 animals, and it is said that he had at least four pack trains. He started packing with mules between Barkerville and Yale in the mid 1860’s with his packing partner, Joe Castillou.

(Above is a historical photo of Cataline.)

In appearance, Cataline was every inch the frontiersman. His hair reached his shoulders. He was broad shouldered, barrel chested, and his usual headgear was a wide brimmed sombrero. Cataline was known to wear the same type of clothing year round: a boiled white shirt, heavy woolen pants, riding boots and no socks. When he had business to conduct, he added a collar, tie and a French hat to his apparel.

One of Catalines best known traits was his unusual hair tonic. His favorite drink was cognac, after each drink he would take a small portion of alcohol and rub it into his hair, saying as he massaged his scalp “a lidda on the insida, a lidda outsida. Bon! She maka da hair grow!”

(Above is a historical photo of Cataline's pack train.)

It was Cataline's claim that he never lost an article, but on one trip, a small parcel disappeared. It happened that one of the packers thought something had gone rotten and had thrown the original package away. The consignee, however, was not the loser, for on his return to Hazelton, Cataline sent a man back with a replacement (one small package containing two pounds of Limburger cheese).

The workforce living and working at Fort St James changed dramatically over the years. While during most of the first century of its operation, the post was run by men from the British Isles and from Eastern Canada. By the early 20th century, many of the people who stayed in the men’s house were local Carrier people working for the Hudson’s Bay Company. This represented a clear change in the roles taken on by the Carrier — from providing mostly goods (salmon and furs) to providing services, such as day labor at the post, or expertise in boat building and transportation of goods.

* * * * *

(Shown above is the Fish Cache on the left, then the Men's House in the middle, and the Interpreter's House on the right.

(Shown above is the Interpreter's House in the 1920's.)

Our next stop was at the Interpreter's House (1889). It was called the Interpreter's House because a Hudson's Bay employee would live here while working as an interpreter for the site.

The history behind the interpreters follows. . .

Among Simon Fraser’s crew was a young man, Jean Baptiste Boucher, who was known under the nickname Waccan. He was one of the most famous interpreters to live and work at the Fort. Over the years Waccan became a well known and respected figure. He worked as an interpreter, an enforcer and some occasions an executioner.

When there was little food Waccan would travel to other camps and return with provisions. If the official head of the Fort left, Waccan would often be put in charge despite not being an officer. On more than one occasion Waccan traveled to avenge the death of a company employee. Waccan lived and worked in the area until his death, over the years Chief factors came and went but Waccan always remained.

James Boucher (shown above) was born circa 1818 at Stuart Lake. He was the eldest son of Jean Baptiste Waccan and Nancy McDougall. Like his father, he was an interpreter for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Saint James on Stuart Lake and was employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company in New Caledonia from 1822 until his death in 1849. James Boucher (shown above) was one of these interpreters who lived in the house for many years. The orginal building burnt down in 1926. Now this building serves as a staff office.

* * * * *

Our next stop was at the Trade Store (1884, shown above). It was the central hub and negotiating center of the region. Here, the pioneers and First Nation people would come to trade furs for blankets, metals, tools, matches, food and so much more.

The Trade Store was also the first post office in the region. The building today is a reconstruction of the original building taken from photographs. The original building was destroyed by fire in 1919, and rebuilt because of its importance to Fort St. James and its heart of the fur trade operation.

The Trade Store was where furs were exchanged for supplies and money. The main room held all the trade goods and an attached office was where the clerk would sleep. You could buy anything from the Trade Store -- food, traps, fabric, and even hair dye.

But the store wasn’t always so well supplied. In the early days, it was difficult to transport materials up to the fort. Also in the early years, things did not always work out the way the fur traders intended. The Carrier people quickly discovered they could get most of the things they wanted from the Trade Store without ever bringing in furs. This was because the traders were in such desperate need of salmon and traded for them from the Carrier in huge quantities. To encourage the trapping and trading of furs, the Company eventually adopted a policy to accept only furs in trade for the most valued store items -- such as blankets or metal pots.

The relationship between the Carrier trappers and the fur traders was often a difficult one. The basic concepts Europeans had about trade were fundamentally different from those of the Carrier. This led to many misunderstandings, especially around debt and gift-giving. While the trade account books recorded the recurring frustration of the traders, it was likely that the fur trappers were often equally frustrated and disagreed about ‘who’ owed ‘what’ to ‘whom.’ Probably the root of the misunderstandings was that, while the Carrier saw trade as primarily a social act, the fur trade companies saw it -- first and foremost -- as a business transaction.

* * * * *

Next, we looked at the Gardens at the Fort St. James National Historical Site that were very important to the fort's existence. As early as May 22, 1811, fur trader Daniel Harmon reported: “We have planted our potatoes, and sowed barley and turnips, which are the first that we ever sowed on this west side of the mountain.”

A few years later Daniel again described the state of agricultural operations at the post: “A few days since, we have cut down and threshed our barley. The five quarts, which I sowed on the first of May, have yielded as many bushels. One acre of ground, producing in the same proportion that this has done, would yield eighty four bushels. This is sufficient proof that the soil, in many places in this quarter, is favorable to agriculture. It will probably be long, however before it will exhibit the fruits of cultivation." He was correct, and it was indeed many years of frustration, experimentation and determination before the Fort St James' garden may have resembled its present appearance.

In the early years, the poor soil and urpredictable frosts hampered efforts to produce crops on a large scale. Though as the years went by the ground was slowly transformed from unyielding clay to soil suitable for farming. George Simpson noted that in 1862 Fort St. james had “vegetables of all kinds" growing in the gardens. Additionally, livestock also played a key role in supplying food for the fort ith about thirty head of cattle and a dozen horses kept at the fort.

* * * * *

At Fort St. James during the early decades, officers and men that were fur traders often saw themselves in an isolated and hostile land.

Daniel Harmon, who was in charge of Fort St. James from 1811-1813, wrote in his journal about life at the post and revealed his attitudes towards his surroundings:

“No other people, perhaps who pursue business to obtain a livelihood, have so much leisure, as we do. Few of us are employed more, and many of us much less, than one fifth of our time, in transacting the business of the Company. The remaining four fifths are at our own disposal. If we do not, with such an opportunity, improve our understandings, the fault must be our own; for there are few posts, which are not tolerably well supplied with books. These books are not indeed all of the best kind; but among them are many which are valuable. If I were deprived of these silent companions, many a gloomy hour would pass over me. Even with them, my spirit at times sinks, when I reflect on the great length of time which has elapsed, since I left the land of my nativity, and my relatives and friends to dwell in this savage country."

Our last stop was at the Officer's House or as it has become known -- the Murray House (1884). The person in charge of Fort St. James would have lived in the Murray House. The house on the grounds today has been recreated to simulate the time period when A.C. Murray lived onsite in the year 1896. In that day, Mr. Murray was considered one of the best, most popular managers, because of his hands-on, fair treatment of the people who worked at the fort.

Some ninety years later, A.C. Murray, the officer then in charge of Fort St. James, elected to retire in Fort St. James rather than to leave the district. Ultimately, his ties to the local community were stronger than his ties to his place of origin. Unlike earlier gentlemen like Harmon, he regarded Fort St. James as his home.

Shown above is a photograph of Mr. & Mrs. A.C. Murray, and their daughter and grandchildren at Fort St. James.

Above is a picture of A.C. Murray on the porch of the Murray House.

We know that A.C. Murray was an avid gardener -- judging by the variety of seeds he ordered. He also owned and played an organ. He taught the Traill children when they were sharing the Officer's House and also used to play the organ on Sundays during Presbyterian services held in the parlor of his home.

Mr. Murray retired in 1914 after 44 years of service and instead of leaving he chose to reside in Fort St James in a house he built on Stuart River. Murray’s wife, the former Mary Bird, lived with him at Fort St James during his tenure at the post. Unlike her husband, who was a Presbyterian, Mrs. Murray was a Roman Catholic, but there is no evidence that either the difference in their faith or the eleven-year gap in their ages caused any conflict between them.

Mrs. Murray was sufficiently independent to travel to Edmonton to visit her family in the fall of 1895. Mr. Murray accompanied her only to Quesnel. From there she proceeded without assistance or companionship to Ashcroft, where she boarded the train to Calgary and from there to Edmonton, a remarkable journey considering the fact that she was subject to frequent epileptic seizures.

We then went inside the Murray House for a look around. Many people have lived in the Murray House over the years. The Traill sisters had lived there as children, when their father William E. Traill was in charge of the Fort. William had arrived at Fort St. James on September 19,1889. He served as Chief Factor from 1889 to 1893. One of daughters recalled, “Our father would always keep a mug in the parlor; in the evening he would pour us some hot chocolate in front of the fireplace.” After the Trail family left the Officer’s House, the Murray family moved in.

Following are pictures from the inside of the Murray House.

(Inside the Murray House was this Queen Victoria portrait -- Queen Victoria ruled the empire back in the day.)

(Shown above is a picture of A.C. Murray and his wife Mary, their daughter Annie, with her two daughters, Jean and Kathleen.)

By the side of the Murray House was a flower garden (see below).

Out back behind the Murray House is where the chickens are kept for the world-class chicken race at the Fort St. James National Historic Site.

A mysterious hush falls over the Fort St. James National Historic Site every day around 11:30 a.m. as the chicken race is about to begin.

You can even bet on the bird with the most pluck! It’s only a momentary lull before cheers burst through the silence and staff everywhere begin pointing in the direction of a shouting brood of people flocking to the famous chicken races.

In lanes lined with chicken wire, the plucky birds have names like Pegasus, Shadowfax, and Bucephalus. Theses are just a few of the names of the world-class racers. But if you were expecting horses, guess again because these racers are much smaller, winged and tend to wake people up way too early. They are definitely chickens!

The chicken coop is attached to a five-lane race course with an automatic door opener (see above). When the “start” button is pressed, the plexiglass door opens, and five chickens race out, each in their own plywood lane.

And the chickens are off! It’s over in about 3 seconds, but it is good, clean, cackling fun!

The crowds even bet chicken bucks on what chicken they think might be a fleet-feathered winner.

In the next enthusiastic 15 minutes, the chickens run anywhere from three to five races each. Proud guests who pick the fastest fowl in a race receive a pin-on “winner’s button" and bragging rights.

* * * * *

Next we stopped briefly at the Home Stretch Diner in the Fort St. James National Historic Site to see if they had chicken on the menu. And of course, one of the daily specials was creamy chicken pasta for $13 CA.

We chose not to get the chicken pasta or a snack at the Home Stretch Diner as we had already eaten lunch before we came to the Fort St. James National Historic Site. And as it was now 3:00 p.m., we decided to go on a scenic drive around Fort St. James.

We then drove by Our Lady of God Hope Church (ca 1873). This church is one of much history and heritage to the town. It is the third oldest church in British Columbia and the first Catholic mission north of Williams Lake. It is a small, one-story, wood church on the shoreline of Stuart Lake in Fort St. James. The church was built by George Blanchet and was the first permanent Catholic mission north of Williams Lake. It has beautifully hand-carved arching woodwork.

The church and its nearby graveyard are valued for their association with Carrier First Nations and with Father Adrien Gabriel Morice, a France-born missionary priest of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who ran a printing press for prayer books and a newspaper for the Carrier people, out of a cabin on the property. Father Morice adapted a Dene writing system of symbols to represent the Carrier language. He is recognized as being the first person to make extensive transcriptions of material in an Athabaskan language.

While Father Morice’s linguistic achievements were celebrated in the past, more recently his use of fear tactics on Indigenous people to break their ties with traditional spiritual practice have come under criticism and Indigenous people are now feeling that Morice bullied them into Catholicism. The historic church was in steady use until 1951, and still holds occasional services today. Headstones in the nearby cemetery still feature the Carrier syllabics that Father Morice worked with.

We then drove along Stuart Lake.

We followed the road past the golf course and around until we got to where we could see Mount Pope. Mount Pope is about 4,659 feet high and composed of limestone.

Our next stop was at the Fort St. James Visitor Center.

This statue (above) was outside the Fort St. James Visitor Center.

Our next stop was at the Sana’aih Market that is located right in Nakazdli Whuten territory on Hwy 27 in Fort St. James. We had heard radio advertisements that they had whole salmon on sale, so we wanted to stop and check it out. We then stopped to get gas at Petro Canada in Fort St. James before heading back to the campground.

Tonight for dinner we had salad topped with grilled chicken fajitas meat.

We just scratched the surface today, but we had a clucking, good time at the Fort St. James National Historic Site!

Shirley & Mel

No comments:

Post a Comment