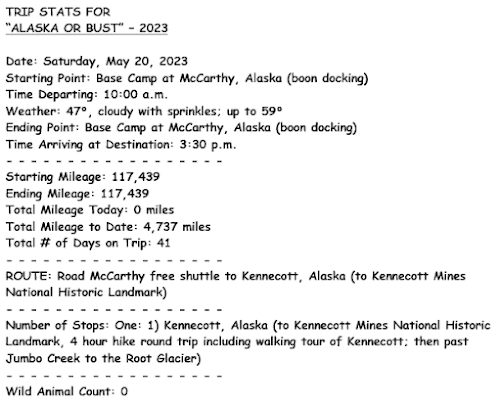

Another beautiful day at Base Camp in McCarthy. Even though the day started out cloudy (at a temperature of 47 degrees) with a few sprinkles, we were not going to let a little rain spoil our parade. We met our free shuttle driver, Jimmy, from the Copper Town Shuttle at 10 a.m. just after we crossed the footbridge, and he took us the grueling five miles along the bumpy gravel road to Kennecott.

Our adventure for the day awaited us. Our plan was to walk around the Kennecott Copper Mines National Historic Landmark Site and then go for a hike to the impressive Root Glacier.

We are on the shuttle with our driver Jimmy on our way to Kennecott. The ride is very bumpy, and we are glad we are just riding along and not having to drive.

* * * * * * * *

HISTORY OF KENNECOTT

Generations of Ahtna people collected native copper found in the Wrangell Mountains, working it into art, utensils and arrowheads. Prospectors flooding to the area in the wake of the ’98 old Rush knew there was copper as well as gold in these mountains, so it as no surprise when the Bonanza Mine was discovered in 1900. Prospectors Clarence Warner and “Tarantula” Jack Smith looked up Bonanza Ridge and saw what appeared to be green pastures, a mountainside stained with the emerald hues of copper ore.

Developing the rich ore body would require tremendous effort, ingenuity, and money. During the early 1900’s, one could not find bigger financial backers than the Havemeyer, Guggenheim, and J.P. Morgan families.

With a young east coast mining engineer named Stephen Birch managing, the three families formed the Alaska Syndicate, which quickly gained a monopoly over the area’s mining operation. When copper from Kennecott reached the world’s markets and the Syndicate became profitable, the group reorganized as the Kennecott Copper Corporation, which still operates other mines around the world today. The Corporation supplied the world with copper for electrification, utilities, industrial development, and munitions for the World War I effort. Kennecott Copper Corporation managed all aspects of their operation with creativity, skill, and at times a heavy hand.

Kennecott, established in 1900, expanded in stages until the mid-1920’s. As mining increased, camp needs grew. Waste rock from the ore, called tailings, helped level the land for building on the valley’s steep hillsides. By 1938, there were more than 100 buildings in camp. But with a limited supply of ore and dropping prices, Kennecott closed that year after producing 200-300 million dollars’ worth of copper and silver.

* * * * * * * *

We learn that copper was forged in the earth and that the prospectors soon discovered how to find it in the contact zone.

A remarkable lode of copper ore near this very spot became known to American prospectors in 1900. Isolated by an imposing landscape, workers developed the camp, mill, mines and railway over the next decade, and Kennecott Mines went into regular production in 1911.

Kennecott Mines contained uncommonly rich copper deposits. The venture proved hugely profitable despite its remote location, thanks to the ambition of its planners and financiers, the ingenuity of its engineers, and the tenacity of its workers. The mines were tapped out and closed in 1938.

Once the railway stopped running, the area was generally quiet despite efforts in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1970s, the communities of Kennecott and McCarthy began growing again. Around the time that the site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986, local residents and others across Alaska worked passionately to rescue Kennecott from the ravages of time. Thanks to their efforts, iconic buildings were stabilized with most of the sites acquired by the National Park Service in 1998.

We followed the self-guided walking tour map above through the Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark.

Kennecott was made a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

The Visitor Center is located in what was the Old School at Kennecott. It was a unique learning environment including students and adults. By 1920, the night school had 126 adult students from 23 countries, while the largest children's class had only 20.

Above is the Kennecott Glacier Lodge.

Above and below are pictures of the Recreation Hall. The

Kennecott Copper Corporation valued a happy and safe workforce. They developed

wholesome activities in the Recreation Hall, such as movie night, dances, and

Christmas parties. Outdoor recreation happened on the company ice rink,

baseball field, handball, and tennis courts. When the miners and mill workers

wanted to experience a less wholesome type of recreation, they traveled five

miles down the hill to McCarthy, where women, dance halls and saloons replaced

tennis and movies.

The Kennecott Wilderness Guides provide glacier hiking tours and glacier ice climbing exhibition, as well as other adventure tours.

I had heard lots of good things about the Meatza Wagon, but as has been the case so far, we are just too early in the season for them to be open.

Above is the new school house in Kennecott.

This is the Refrigeration Plant. It makes you wonder why would a community with a glacier in their backyard would need a

refrigerator? Well they didn’t, however the innovative corporation always

experimented and took advantage of the latest technology and materials they had

available. In this case the cooling ability of compressed ammonia was used. They had access to the railway which helped move food supplies in and out of the building and there are still some hanging meat

hooks.

East and West Bunkhouses – Kennecott was generally a community of transient men. Some worked for just three months in order to pay off their train fare; others

stayed several years. Men lived two to a room and paid around $1.25 a day for

room and board. There were several bunkhouses scattered throughout the mill and

mine sites. Kennecott hosted multinational crews including workers from

traditional mining backgrounds such as Norwegians, Swedes, and Irish workers.

Japanese cooks provided meals and other camp services. Single women who worked

in camp lived separately on the third floor of the Staff House, called “No

Man’s Land”.

Below is the General

Store and U.S. Post Office. This building connected the remote residents of

Kennecott to the outside world. Families could purchase just about anything

that could be found in the “lower 48.” If the store didn’t have it, an order

could be placed through popular catalogs. However, they would have to be

prepared to wait a month or more for a special order to arrive.

Since the general store wasn't open, all we could do was look through the window and see the neatly lined up canned goods on the shelves.

Our first glimpse of the historic icon -- the copper mines.

Railroad depot and the National Creek behind it. It flooded during the week of October 9, 2006 when over 4 inches of rain came in the Kennecott area in a matter of hours. The National Creek exceeded its banks causing significant erosion and a shifting of the channel to the north. This shifting channel destroyed the historic Assay Office and heavily damaged the Hospital, West and National Creek Bunkhouses which paralleled the current channel stream. The historic Railroad Trestle was also heavily damaged and had to be demolished (but because it played such a significant role in the development of Kennecott, it was replaced).

This information board talks about how they have worked at stabilizing the copper mine mill building. Since the 14-story, 34,500 square foot mill building was constructed on a series of terraces that stair-step up the 36 degree slope. The current repair work focuses on the lower seven terraces and includes repairs to the timber foundation through the construction of a secondary system of tieback anchors and vertical supports to halt collapse in the critical areas of the building.

The view of the Kennecott Glacier is truly a badland of ice -- an expanse of rock, silt mounds, exposed fins, lateral moraines, strange landforms and patches of exposed ice. This glacier dominates all views west of the historic mill town site of Kennecott and is basically located across the street from the Kennecott Glacier Lodge in the heart of the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. The Kennecott Glacier has been receding from its terminus for years, and it immensity and ruggedness remains a magnificent sight filling the four-mile-wide valley like a mighty river. The glacier stretches uphill to its source on 16,390-foot Mount Blackburn, Alaska's fifth tallest peak.

The Historic Copper Mine Mill buildings -- some in ruins.

The Machine Shop is in front of the Power Plant (which is the building characterized by the four smokestacks.) The Machine Shop was used to keep Kennecott operating efficiently. The men kept the machines functioning and the machines kept the mines and mill productive. Equipment in need of repair traveled from the north side of the Mill building on a narrow-gauge service tram and crossed the main railway via a drawbridge to the Machine Shop. Remnants of the drawbridge support are still standing just north of the Mill building.

Kennecott required power to support both the mill town and the mines several miles up the mountain. The Power Plant was constructed in three stages between 1911 and 1924. Disaster struck in August 1924 when the plant burned down, but it was quickly rebuilt and back in operation in October 1924. The plant used two diesel generators, a Westinghouse steam turbine, and a Pelton waterwheel to provide power and steam heat. Steam and electricity traveled to outlying buildings and homes through utilidors. The warm utilidors were built under wooden walkways, which kept them free of snow and ice in the winter.

The transformer shop is above.

Above cottage is the NPS cottage. Only l0% of Kennecott's population lived in cottages with their families, and middle and upper management level employees paid about 25% of their income to the company to live in these small cottages with their wives and children. Cottage position, plumbing, room size and building colors all reflected status in the remote town -- the higher up the home (cottage), the higher up they were in the chain of command.

After we finished viewing the historic town of Kennecott, we headed toward the Root Glacier Trail. It is a trail that weaved in and out of the forest parallel to the glacier, crossing creeks, where we could enjoy views of peaks and glaciers in the valley. There was a primitive camping area with a bear box, just past Jumbo Creek at 1.5 miles. From there we turned right and kept following the trail until we came to the best sight of Root Glacier.

As we began the trail, we were greeted with our first pile of moose scat "poop" (see below). We saw many more piles along the path to Root Glacier.

The trail to Root Glacier was covered with snow in many areas.

And we crossed a few creeks.

More snowy patches getting a little deeper, but doable.

Views of the Kennecott Glacier and mountains along the way.

Beginning to see tailings of Root Glacier (see white patches of snow below).

We're finally to the Jumbo Creek crossing.

Mel on the walkway across Jumbo Creek.

Root Glacier is getting closer.

Shirley and Mel in front of Root Glacier.

Closeup of blue ice on Root Glacier.

Views on the trail back from Root Glacier -- mountains and Kennecott Glacier.

Mel on walkway across Jumbo Creek on our way back.

We're almost back to the historic town of Kennecott.

NPS cottage and the Power Plant are ahead.

Just a few more pictures of the Kennecott Mine and Mill.

One last glimpse at Kennecott Glacier. We then boarded the shuttle and Jimmy took us back to McCarthy to the footbridge in front of Base Camp.

We then sat outside and enjoyed our fantastic view from our campsite one more evening. We had chicken & veggie "hobo meals" on a charcoal fire. Simply delicious!

What a fantastic evening in our "semi-private" campsite in Base Camp at the foot of the Kennecott Glacier.

Pleasant dreams!

Shirley & Mel

Love the photosnand history. Mel looked so tiny in that picture above the water. Amazing.

ReplyDelete